|

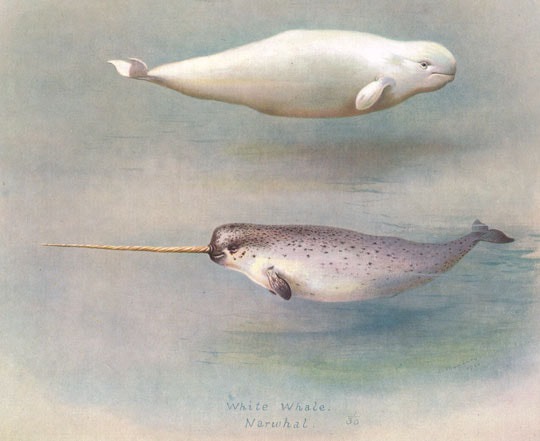

For some strange reason, one of my favorite parts of the classic movie Elf (with Will Ferrell) is the brief scene involving Mr. Narwhal. I can't explain it, but it cracks me up every time (Bye, Buddy. I hope you find your dad.). Here's a question for you... Do you remember the exact moment you learned that narwhals are actually real? I'm being serious here. I had seen pictures of them when I was a kid, but I just assumed they were some kind of mythical beast, like the giant squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea or the crazy monsters they used to draw in the oceans on those really old maps. Perhaps learning that narwhals are real is part of how I became so fascinated with animals. What the heck is a Narwhal? Narwhals are toothed whales. Toothed whales are those that... well, they have teeth. The group includes dolphins, porpoises, beluga whales, killer whales, sperm whales, and the beaked whales. Hmm... yes, narwhals are in the toothed whale group, but oddly they only have a few teeth, and they don't chew with those teeth at all. They gum their prey. By the way... if you were a whale, and you were NOT a toothed whale, you would be a baleen whale. All whales fit into one or the other of these two major groups. The word narwhal literally means corpse whale. Nar is an Old Norse word that means corpse. Narwhals got this name because their skin is usually mottled gray (like the skin of a drowned sailer), and because in the summer these whales often float at the surface without moving (again, like a drowned sailer). Often called unicorns of the sea, Narwhals are unique among whales because the males possess a very long tusk, which looks like a unicorn horn. Well, actually that's a silly comparison, because unicorns don't exist. It would be better to say that narwhal tusks look similar to the way artists typical draw horns of the mythical unicorn. Perhaps because people came up with the idea of unicorns after observing narwhals. Amazing facts about Narwhals Let's talk about this crazy tusk first. As I stated above, usually only male narwhals have these. The tusk is actually a modified canine tooth (remember I said they only have a few teeth?). It grows out from the left side of the upper jaw, right through the lip, and it forms a spiral as it grows. These tusks never stop growing (well, until the whale dies, that is), and they can get up to 10 feet (3.1 m) long! For comparison, male narwhals, not including the tusk, are about 15 feet (4.5 m) long and weigh 3,500 pounds (1,590 kg). Females are slightly smaller. Usually, it's only the left canine tooth that grows into a tusk. But in one of about every 500 male narwhals the right canine grows out as well. So there are actually narwhals that have TWO tusks. Also, about 15% of the females grow a tusk (although only one female has ever been found that had two tusks... that female was collected in 1684). Check out this narwhal skull and tusk: What in the heck is the function of this bizarre tusk? That's a bit of a mystery. Scientists have come up with plenty of explanations. One idea is that the tusk is used as a weapon against predators (polar bears, orcas, and sharks) and to spear fish for their dinner. Or maybe they use it to dig for prey on the ocean floor. Another idea is that they use it to puncture the surface ice to make breathing holes (narwhals live mainly in far north arctic waters). Some scientists have suggested the tusk is an acoustic organ (tusks are hollow, and narwhals communicate with clicks and whistles). One thing is for sure. The tusk is not essential for survival—most females don't have them, and the females live longer than the males. The leading theory is that the tusk is for sexual selection. Males are often seen with their heads out of the water, hitting and rubbing their tusks together as if they are sword fighting. This is called tusking, and scientists have often assumed this is a way for males to establish dominance. But wait! There's more to this mystery. A 2014 study found that narwhal tusks contain millions of highly sensitive nerve endings. These nerve endings are particularly suited to detect ocean water conditions. So, scientists have suggested that when males rub their tusks together, they are actually exchanging information about the nature of the water they have recently traveled through. Whoa... that's cool. And there's more! In 2016, drones were used to film narwhals, and for the first time ever they were observed using their tusks to stun fish (arctic cod), which they would then eat. Check out this video showing this feeding behavior. My guess is that narwhal tusks are multi-purpose tools. Most likely, they are used for sexual selection, but they are apparently useful for a variety of other tasks. They are the Swiss Army knives of the whale world! One more rather odd thing regarding a narwhal tusk. On November 29 there was a tragic and violent attack that concluded on London Bridge. A knife-wielding man began attacking innocent people at a prison rehabilitation program. Darryn Frost, a civil servant in Britain’s Justice Ministry, grabbed a long narwhal tusk from the wall in Fishmonger's Hall (beside London Bridge), and confronted the man, eventually (along with several others), chasing the man onto London Bridge and subduing him (the attacker was then shot). Anyway, this is the only instance that I know of in which someone used a narwhal tusk as a weapon. Frost is now considered a hero. The narwhal's closest relative is the beluga whale (which looks like a white narwhal without a tusk). They are so closely related, in fact, that they sometimes mate and produce hybrid offspring. This is very rare, though. In Greenland in 1990, an unusual whale skull was found. The skull was unlike any scientists had seen before, but it had characteristics of both the beluga whale and the narwhal. Finally, in 2019, DNA analysis proved that the skull was indeed a hybrid between the two species. Below is a 1920 illustration of the two species. Fortunately, although narwhals are very secretive and difficult to find, they are designated as a species of "least concern" (not threatened or endangered). Scientists estimate the population to be about 125,000. However, arctic sea ice is melting at an alarming rate, which will result in more ships moving through the waters where narwhals live. Unfortunately, narwhals are vulnerable to ships. They become extremely frightened and stressed when ships pass by. Also, their habit of lying motionless at the surface results in collisions. But for now, they seem to be doing okay. So, the Narwhal deserves a place in the L.A.H.O.F. (Lollapalooza Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The first documented use of the word lollapalooza was in 1904. It is considered an Americanism, and it refers to something or someone truly remarkable. Oddly, no one seems to know exactly how the word originated. Lollapalooza is also the name of a popular annual music festival. How did the festival get this name? Legend has it that Perry Farrell (of the band Jane's Addiction) named the festival Lollapalooza in 1991 after hearing the word in a Three Stooges short film. So, lollapalooza is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Scene from Elf - ABC News Single Narwhal on blue background - University of Washington Magazine Narwhal skull and tusk - Dinosaur Corporation Male narwhals tusking - World Wildlife Fund Darryn Frost with narwhal tusk - Times of Israel Narwhal and Beluga illustration - Wikipedia

0 Comments

The other day, Trish shared a post with me that featured several photos of a flower mantis. The creature was so beautiful that at first I wondered if it was even real. Well, flower mantises are indeed real. Somehow I had never known about them before! So, I decided to feature the flower mantis today, in case some of you have never heard of them. Yes, they are real. By the way, the person who found the above female flower mantis (in the Nkutu Valley, South Africa) named it Miss Frilly Pants. What the heck is a Flower Mantis? The flower mantises include about 1,800 species (wow!), most of them in the family Hymenopodidae. They are found in East Africa, as well as in South and East Asia. Like all mantises, flower mantises are extremely skilled and deadly predators. This, in fact, is why they look like flowers. They use a strategy called aggressive mimicry, which can most easily be described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. More on that below. I wish I could provide photos of all 1,800 species, but I'll have to settle on just a few. Amazing facts about Flower Mantises Flower mantises are tricky predators. As I mentioned above, they use aggressive mimicry. This is not the same thing as camouflage (which is blending into the surroundings so as to not be detected). Aggressive mimicry is when a predator is disguised as something that is harmless to its prey. In fact, it is usually something that attracts its prey. So, instead of blending into the surroundings (camouflage), the predator stands out so that it is very visible. It just isn't what it appears to be. Another example of aggressive mimicry is the alligator snapping turtle. The turtle sits on the bottom of a stream or pond, opens its mouth, and wriggles its pink tongue. To a fish, the tongue resembles a wriggling worm. The fish swims right into the turtle's mouth, and.... snap! Hence the name, snapping turtle. Predators that use aggressive mimicry don't have to go hunting for their prey. They simply sit and wait for the prey to come to them. By looking like flowers, flower mantises attract pollinating insects that like to feed on the flower nectar. The insects see the "flower," they fly right up to it, and... snap! Check out the orchid mantis below, beside an actual orchid that it mimics. Scientists have been fascinated by flower mantises for well over 100 years. One of the first people to describe them (although incorrectly) was the travel writer James Hingston in 1879. Hingston mistakingly thought that the flower mantis he was watching was actually an insect-eating plant: "I am taken by my kind host around his garden, and shown, among other things, a flower, a red orchid, that catches and feeds upon live flies. It seized upon a butterfly while I was present, and enclosed it in its pretty but deadly leaves, as a spider would have enveloped it in network." So, the mantis's mimicry worked so well that it even fooled this human observer. I feel compelled to further explore this type of mimicry. Actually, for a long time scientists mistakingly believed that flower mantises were an example of cryptic mimicry. In other words, scientists assumed the mantises looked similar to flowers so that they could hide among the flowers and wait for insects that were attracted to the flowers. There are plenty of examples of such cryptic mimicry, such as the crab spider in the photo below, which has just caught an unsuspecting wasp. Keep in mind that the wasp was attracted to the flower itself, not to the spider. For many years, this is what scientists believed flower mantises were doing. Eventually, however, they began to realize this isn't true of the flower mantis. Flower mantises do not hide within the flowers. In fact, they don't hide at all. They usually sit upon a background of green leaves so that they stand out. They are not trying to hide. They want to be seen. And this gets even stranger. It turns out that flower mantises are even better at attracting insects than the flowers themselves. If you put a flower mantis side-by-side with a similar flower, insects will visit the mantis more often than the flower. What? How can that be possible? We have to get into a bit of bug psychology to understand it. When we humans look at a flower mantis, it might fool us at first, but as we look closer, we see that something isn't quite right, and soon we figure out that it is an insect instead of a flower. That's how our brains work. Bees and flies, on the other hand, do not have this capability. They simply see the mantis's color, and they think, "Ooh, a flower... yummy!" Then they dart right in for some nectar, and... snap! So, insects are simply attracted to the specific color and the general shape of a flower, not really the details. The thing is, flower mantises usually do not look like any one specific type of flower. Instead, they have the characteristics of several kinds of flowers. In other words, they are structured to look like a generalized flower. And they attract more insects because some insects are specific in which type of flower they like... so, it is helpful to the mantis to look like several types! Flower mantises are actually the first animals we've ever discovered that capture their prey by mimicking a complete flower. Unlike other mantises that grab prey insects that are crawling on the ground or on a plant, flower mantises grab their prey out of the air. This happens in a fraction of a second, and the mantises are really deadly in their aim. Check out this cool video about flower mantises. Since these insects are so amazing to look at, I'll wrap this up by showing a few more examples: So, the Flower Mantis deserves a place in the R.A.H.O.F. (Ripsnorter Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The first documented use of the word ripsnorter was in 1840. It is considered an Americanism, and it refers to something or someone extraordinary ("That fiddler played a ripsnorter of a song"). It can also refer to something intense or violent ("That was a ripsnorter of a storm"). Flower mantises are definitely extraordinary, and they are also extremely powerful predators. So, it fits. Ripsnorter is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Flower Mantis #1 - Waterfall Retreat & Environmental Centre Facebook Page Orchid mantis and orchid - Igor Siwanowicz via The Conversation Crab spider - Olaf Leillinger/Wikimedia via The Conversation Purple spiny flower mantis - iNaturalist via Twitter Very thin flower mantis - PXFuel - Creative Commons Flower mantis on tip with buds - Roger Meerts/Shutterstock via Discover Magazine Flower mantis on rolled-up leaf - Thinkstock via Mentalfloss |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed