|

My last post featured the Maned Wolf, a bizarre and little-known mammal. The Fossa also fits that description—a strange mammal that many people have not even heard of. What the heck is a Fossa? The fossa is not a cat (feline) or a dog (canine), although in some ways it resembles both. It is actually a relative of the mongoose. Fossas are medium-sized (15 to 26 pounds, or 7 to 12 kg) carnivorous mammals that live in the forests of the large African island of Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean. The name fossa is actually pronounced foo-sah, although many people also pronounce it as foosh. Amazing Facts about the Fossa The fossa is the largest carnivorous mammal native to Madagascar. Its total nose-to-tail-tip length is about six feet (1.8 m), with half of that length being its tail. As Madagascar's top predator, the fossa's favorite prey are various species of lemurs. In fact, fossas are often described as lemur specialists, and they can kill and eat lemurs that weigh 90% of the fossa's own weight. However, they also sometimes eat just about anything else they can catch, including small mammals (particularly rodents), birds, lizards, snakes, frogs, insects, crabs, and even fish. Most animals prefer to hunt either during the day or during the night, but the fossa seems to be happy hunting day and night. They also are just as skilled at hunting in trees as they are hunting on the ground. This ability to eat a variety of prey, as well as the ability to hunt anywhere and anytime, has helped the fossa to live in almost every habitat across Madagascar. Even so, in some areas they are extremely rare and seldom seen by people. When scientists studied the content of fossa droppings (which look like a cylinder with twisted ends... kind of like a Tootsie Roll wrapper), they also found seeds. The seeds may have been in the stomachs of the lemurs the fossas had eaten, but more likely they were seeds from fruits the fossas ate in order to get the water from the fruits. This last idea is supported by the fact that seeds are more common in the droppings during the dry season. The fossa's scientific name is Cryptoprocta ferox. Look at the genus name Cryptoprocta. Crypto means "hidden," and procta refers to the anus (think proctologist). So, this creature was named "hidden anus." Why? Well, the fossa has quite a few scent glands it uses for communication, especially for marking its territory. Some of these scent glands are just outside the anus, and they are enclosed within an anal pouch that encloses the anus, with a slit opening allowing the creature to defecate. So, the anus is hidden--Cryptoprocta! Fossas are apparently proud of their scent glands, and they love using them! They are solitary animals (except when mating and raising young), and they go to great lengths to mark their territories using their scent glands. They enthusiastically mark trees, rocks, grasses, and the ground. Each of these marks is basically a No Trespassing sign for other fossas. Okay, it's time to have "the talk." I'm referring, of course, to fossa mating habits. These creatures have some rather unusual reproductive strategies. Fossas are polyandrous, which means the females have more than one male mate (polyandry can be compared to polygyny, in which one male has multiple females). With the fossa, mating is all about the location. Mating typically takes place on a solid, horizontal tree branch, an average of 66 feet (20 m) above the ground. Yikes! That's a long way to fall, so this can be a dangerous activity. A particular tree branch will be used year after year, often by numerous females. Think of it as a singles bar, where young men and women go to hook up with a partner. Often, as many as eight males will hang around the spot, waiting for a female to show up. The females, who usually return to the same tree year after year, will arrive there one at a time, and each female will stay there for as long as a week. During that week, the female will mate with numerous males, one male at a time. The female chooses one of the males, signaling him with mewing sounds. Mating takes about three hours, and the process requires extreme acrobatic balance to prevent falling. After mating with the same male several times, which takes a total of about 14 hours, the female will signal another male that it's his turn. This goes on for up to a week, and then the female leaves the area, which means it's time for the next female to arrive and stay for another week, repeating the process. Unless you are offended by watching such things, check out this video of fossas mating. The female will give birth to up to six pups, which are very small, blind, toothless, and helpless. The pups do not become independent until they are a year old, and they are not sexually mature until they are three to four years old. As you can probably imagine, the pups are pretty darn cute. So, the Fossa deserves a place in the B.A.H.O.F. (Bonny Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word bonny (or bonnie) originated in the mid 1400s. It's a Scottish adjective meaning "pleasing to the eye; handsome; pretty." The word is thought to have come from the Old French word bon, which means "good" (as in bon appétit, which literally means "good appetite"). The French word was in turn derived from the Latin word bonus, also meaning "good." Words derived from bonny include the adverb bonnily (the fossa ran bonnily through the forest) and the noun bonniness (the fossa possesses a great deal of bonniness). So, bonny is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Fossa lying on its belly - DepositPhotos Fossa in tree with black background - DepositPhotos Fossa face - DepositPhotos Baby fossas - San Diego Zoo

1 Comment

This is one of those animals I chose simply because it looks so strange. It's a dog-like mammal that appears to have the body of a wolf, the face of a fox, the legs of a deer, and it has urine that smells like marijuana. Being this strange, it's surprising that few people have even heard of this animal (I just learned about it a few days ago). It's time to change that! What the heck is a Maned Wolf? This name is kind of unfortunate because the word "wolf" has negative connotations for many people. The maned wolf is not a wolf, and even though it resembles a fox on stilts, it is not a fox either. Instead, it is a canine species that is in its own genus (Chrysocyon, which means "golden dog") and is not closely related to other living canines. So, it is not a fox, wolf, coyote, dog, or jackal. Maned wolves live in South America, primarily in south and central Brazil and into Paraguay, Argentina, and Bolivia. Unlike many other canines, these creatures are omnivorous, meaning they eat substantial amounts of both plants and animals. They get their name from the noticeable mane of hair on their neck, which stands up straight when they sense danger. Amazing Facts about the Maned Wolf First let's figure out those long legs. Although maned wolves are not particularly heavy animals (average 51 pounds, or 23 kg), these legs make the creature the tallest of all the wild canines. Why would a canine need legs that long? It has to do with the habitat these creatures live in. They inhabit grasslands, savannas, marshes, and wetlands, and it is thought that long legs help them see over the tall grasses. Their long legs also probably help them run through the grasses. Unlike real wolves, maned wolves do not form packs. They live most of their lives alone, and they hunt alone. They are considered crepuscular, which means they are most active during the twilight hours. You may have noticed from the photos that maned wolves have exceptionally large ears. This helps them with their unusual hunting techniques. They will stand still and rotate their ears, listening for small creatures moving around in the tall grass. If they hear something, they tap the ground with a front foot to flush the prey creature out, then they pounce on it. They typically eat rodents, rabbits, insects, birds, and sometimes even fish. The really surprising thing is that the maned wolf's diet is 50% plants! This is highly unusual for a canine species. They feed on sugarcane, fruits, and other plants. In fact, studies show that they eat at least 116 different plant species. The most common food item for the maned wolf is a fruit called the wolf apple. Astoundingly, this tomato-like fruit can make up 40% to 90% of the maned wolf's diet. Maned wolves seem to love these, and they regularly seek them out. Part of the fruit's appeal is that they grow all year, whereas most other fruits in the maned wolf's habitat are only available in the rainy season. Below is the wolf apple. The seeds of the wolf apple pass right through the creature's digestive system and are deposited on the ground along with a nice pile of fertilizer. This makes the maned wolf an important means of seed dispersal for this plant. So important, in fact, that this relationship between the maned wolf and the plant is considered a symbiotic relationship, in which the two species rely on each other to survive. An interesting twist to this symbiotic relationship is that maned wolves will often seek out a leafcutter ant nest before defecating. It will then poop directly onto the ant mound. Why? Because this helps the wolf apple seeds to germinate. How? Well, the ants need the dung as fertilizer for their underground fungus gardens (Did you know ants grow underground fungus gardens? That in itself is a fascinating story for another newsletter!). The ants carry the valuable dung below ground, but they don't need the wolf apple seeds, so they carry those away from their nest and place them in ant trash piles. For some reason this helps the seeds grow. So... the symbiotic relationship actually includes three species: the maned wolf, the wolf apple plants, and the leafcutter ants. Actually, four species if you include the fungus farmed by the ants. These kinds of relationships in nature fascinate me! Because other canines do not eat many plants, zoos were slow to figure out how to properly feed captive mane wolves. Historically, they fed them mostly meat, and the maned wolves often developed bladder stones. Eventually, as the maned wolf became better understood, zoos switched to a diet with more vegetables and fruits, resulting is healthier animals. The maned wolf has a strange vocalization for communication. It's called the roar-bark, and few people have the opportunity to ever hear it. Check out this video of a wild maned wolf using its roar-bark. Speaking of communication, what's the story on this urine with a strange smell? Besides their roar-bark, maned wolves use their urine as a form of communication. For example, they mark their territories with the strong-smelling urine, as a way to warn other maned wolves to stay away. They also mark their paths to the spots where they have buried prey animals they couldn't eat in one meal (they do sometimes take larger prey). Below is a maned wolf urinating on a tree to mark its territory. As I said above, this is special urine, with an unusual smell. The urine releases pyrazines, a compound that creates a powerful odor that smells like marijuana smoke. Some people also say it smells like hops. As it turns out, pyrazines happen to be present in both of these types of plants. Here's an interesting story of an incident that occurred at the Rotterdam Zoo in South Holland province (in The Netherlands). Dutch police were called because zoo visitors were reporting that someone was illegally smoking pot in the zoo. When the police investigated, they learned the smell was coming from urine in the maned wolf cage! One more tidbit of information. We can't discuss a canine species without looking at the puppies, can we? Who doesn't like puppies? Well, actually they're called cubs, but I like the word puppies. Although maned wolves usually live alone, you probably know they have to violate this rule now and then if they want to propagate. After a gestation period of about 65 days, the female gives birth to a litter of two to six black pups. Yep, the pups have black fur for about the first 10 weeks before their fur turns red. The parents stay together while the pups are young so they can both take care of the little furballs (although the females do most of the care). After the pups are weaned from breastfeeding, their parents feed them regurgitated food. Yeah, they eat barfed-up animals and plants, like a baby bird. Everyone deserved a warm meal, right? So, the Maned Wolf deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F. (Superlative Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word superlative originated in the late 1300s, and it came from the Latin word superlativus, which meant "extravagant, exaggerated, hyperbolic." Superlative today is used as an adjective to describe something as "of the highest kind, quality, or order; surpassing all else or others." It is also a noun used in grammar, referring to the highest degree for comparison. For example, take the word cool. The comparative form is cooler, but the superlative form is coolest. And you have to admit, the maned wolf is the coolest. So, superlative is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

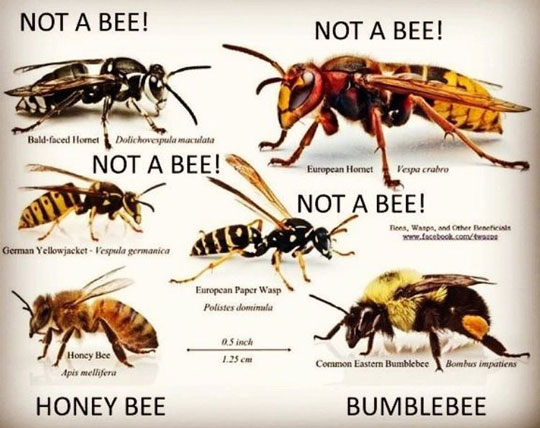

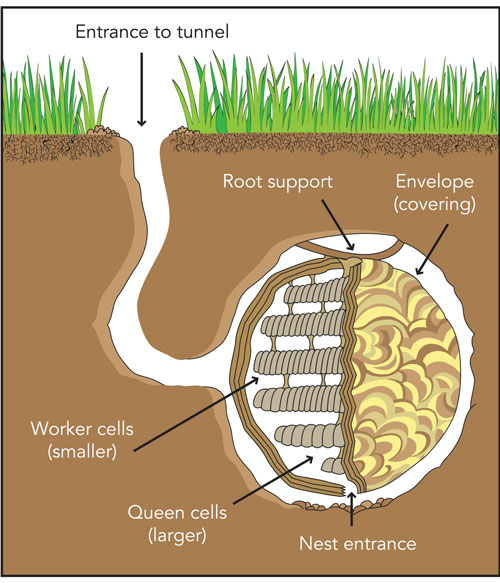

Maned wolf #1 - DepositPhotos Maned Wolf #2 - Wikimedia Commons Wolf Apple - Tribal Simplicity Maned wolf in zoo - DepositPhotos Stock Images Maned wolf urinating on tree - Wikimedia Commons Maned wolf mother with cubs - DepositPhotos Stock Images In my last newsletter two weeks ago I featured the prairie dog because prairie dogs make a (very surprising) appearance in my new novel Hostile Emergence. I'm continuing that theme with another animal that appears (in large numbers) in the new book. This animal is the yellowjacket. What the heck is a Yellowjacket? Yellowjacket (or yellow jacket) is the name used to refer to a group of wasp species that are predatory and live in social colonies. Yellowjackets are fairly small wasps, and they typically have yellow and black markings. Something I can tell you about them from personal experience—yellowjackets are mean, and their stings are painful! Amazing Facts about Yellowjackets Okay, first we need to sort out exactly what yellowjackets are, compared to other bees and wasps. Sometimes people mistakenly call them bees because they are about the size of a honeybee. Bees are different from wasps in a number of ways. For example, bees are plump and hairy compared to wasps. Wasps are slender, with a very thin waist. Wasps are shiny, with a smooth body surface. Bees have thick hind legs for collecting pollen, wasps do not. When wasps fly, their legs hang down, but bees' legs are tucked against their body. Bees have a barbed stinger, which usually causes the stinger to pull loose from their body after they sting, so they can only sting once (which is why they are less aggressive than wasps). Wasps can sting over and over again (so they tend to be much more willing to sting). Bees feed on flower nectar and pollen, whereas wasps are predators that kill other insects and take them back to their nest to feed to their young (although they feed on nectar and sweet fruits when they are not caring for their young). So, now we know yellowjackets are not bees, but what makes them different from other wasps? What makes them different from hornets, for example? This is confused by the fact that some yellowjackets have the word hornet in their name, such as the bald-faced hornet in the picture above. True hornets, though, are much larger than yellowjackets (see the European hornet above). Why does the bald-faced hornet have that name if it's actually a yellowjacket? Good question. Some people call it a blackjacket, which I think would be a less confusing name. One reason bald-faced hornets have been given that confusing name is that they typically make nests that are exposed and above ground (most yellowjackets make nests below ground or in enclosed cavities). Here is a bald-faced hornet nest I found on the back of our garage. Another reason bald-faced hornets have been given the confusing name is that they are black and white, while other yellowjackets are black and yellow. As I said above, typical yellowjackets make their nests below ground (as do the yellowjackets in Hostile Emergence). These below-ground nests usually only last one warm season, then the yellowjackets die off (except for the new queens). During that one season, the nest grows to about the size of a basketball, and can have several thousand wasps. In some areas where the winters do not get so cold, the nests can survive for several years, growing much larger. Below is an excavated two-year yellowjacket nest. Let's imagine for a moment that you are walking across your yard. You do not realize that buried below your feet is a massive yellowjacket nest like the one pictured above. You cannot tell it is there because the tiny entrance hole at the ground's surface is only a centimeter across. Perhaps you see a few wasps flying in and out of the tiny hole, so you stomp on the hole to kill some of them. This is a bad idea. Why is it a bad idea? Because yellowjackets are notoriously aggressive when their nest is threatened. Not only that, but they can detect vibrations in the ground. You might have hundreds of angry yellowjackets swarming out of the hole, ready to sting. This can be a painful experience, and if you happen to be allergic to their venom, it can even be dangerous. Last summer I pushed my mower over a below-ground yellowjacket nest, unaware of the nest's presence. Fortunately, I was stung only three times, but each of those stings resulted in massive swelling for several days. So, even if you aren't terribly allergic to yellowjacket venom, numerous stings can still be dangerous or even deadly. And, as if that weren't enough, yellowjackets can bite as well as sting! They have jaws for capturing their prey, and they can use those jaws to bite you and hang on, making it difficult to swipe them away with your hands. They can cling to your skin or clothing, stinging repeatedly. Nasty little devils! Yellowjackets are actually more aggressive in the fall, as the weather is turning cold. Why? Because, as I said above, the wasps die out when the weather turns cold (except for the new queens). They die because their food source (other insects, as well as nectar and ripe fruits) is disappearing. So, the wasps are starving to death. This makes them grouchy, because they are constantly working harder to find enough food. In the spring, there are fewer yellowjackets, and they have plenty of food, so they are not as aggressive. Yellowjackets also have a bad habit of attacking valuable honeybee colonies. They target honeybees, killing and eating all the adults and larvae, then feasting on the honey for dessert. This is more likely to happen in the fall, when honeybees are more sluggish in the cold compared to yellowjackets. In Canada there was a report of yellowjackets wiping out 100 of the 300 beehives of a commercial beekeeper. Each of those colonies had 50,000 honeybees! You're probably wondering if I have anything good to say about yellowjackets. I do. After all, they are Awesome Animals. Some of the awesomest of all animals are those that can be dangerous (sharks, venomous snakes, and black widow spiders, to name a few). Sometimes an animal's most amazing adaptations are those of self defense and predatory skills. So, although I have a healthy respect for yellowjackets, I still appreciate their amazing characteristics. I'll point out that many of the insects yellowjackets prey on are considered agricultural pests. Yellowjackets may not be beneficial to honeybee colonies, but they are beneficial to farmers. Yellowjackets also often feed on human garbage, typically items with high sugar content. Let's wrap this up by examining the fascinating life cycle of these insects. Yellowjackets are social wasps, meaning they live in colonies in which individuals have specific roles, with specific body types for each role. Yellowjacket roles include queens (females), workers (females), and drones (males). In climates with a cold season, a colony typically lasts only one year. A colony is started by a single fertilized queen. After surviving through the winter in a sheltered place, a queen will find a suitable place to start a nest, usually an existing hole in the ground (like a rodent burrow), but sometimes in a cavity of a stump or even a house or barn. She will build a small paper nest and lay about 50 eggs. After the eggs hatch, she hunts insects and brings the food back to feed the larvae. When the larvae are full grown, they form a pupa and eventually emerge as adult females (workers). As more workers emerge, they get busy and start expanding the nest. They also go hunting for food for the new larvae, and they defend the nest (all yellowjacket females can sting, but the male drones can't). The colony and nest continue growing, often resulting in 5,000 wasps and a nest with up to 15,000 cells. Eventually, the workers start creating larger cells, in which new queens will grow, as well as male drones. The new queens and the drones then leave the nest and go out into the world to mate. After mating with new queens from other colonies, the males quickly die. After mating with drones from other colonies, the new queens store up body fat and find a safe place to survive the winter. All the wasps, except for the new fertilized queens, will then die. The nest decomposes over the winter (the wasps do not reuse the nests). In the spring, the new fertilized queens start the cycle all over again. Check out this video about the yellowjacket's nest and life cycle. Note: although yellowjackets typically build their nests below ground, sometimes a queen will start a colony in a cavity of a human-made house or other structure, as you will see in this video. So, the Yellowjacket deserves a place in the G.A.H.O.F. (Groovy Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The term groovy originated in the jazz culture of the 1920s. It probably originated from the physical groove in a record, in which the needle drags. However, it was mainly used to refer to the groove of a song (how the song sounded and felt to the audience). Disc jockeys would say things like, "I'm going to play some good grooves" (or "hot grooves"). Eventually, starting in 1941, the word groovy began to be used as slang, meaning "marvelous, wonderful, or excellent." This usage became really popular in the 1960s, but by the 1980s it was only being used as a humorously outdated term. I still hear people using the word, especially people much younger than myself, so perhaps it will become popular again. So, groovy is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Yellowjacket #1 (on white background) - DepositPhotos Stock Images Large excavated yellowjacket nest - Wikipedia Creative Commons License Cartoon yellowjacket - DepositPhotos Stock Images Yellowjackets on apple core - DepositPhotos Stock Images Yellowjacket nest diagram - Marin/Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed