|

In my new novel, Foregone Conflict, Skyra, Lincoln, and the team find themselves in a strange world in which Neanderthals and humans both exist. The more they learn about the people of this world, the stranger things become. The people here are oddly fascinated by spiders. Not just any spiders, though. They are fascinated specifically by social spiders, an amazing group of spiders that live in huge colonies (instead of individually, like most spiders do). So, today, to celebrate the release of Foregone Conflict, I am featuring social spiders! What the heck are Social Spiders? It's important to remember that, as a rule, spiders are antisocial. They like to be alone. They hunt alone, they aggressively defend their webs, and many of them actually eat their own mates (which is very rude). Consider Shelob, the monstrous spider that attacks Frodo in The Lord of the Rings. Shelob hangs out alone in the caves of the Mountains of Shadows, waiting for foolish hobbits or orcs to wander too close. But there are some species of spiders, particularly in tropical areas with an abundance of insects, that have overcome these "lone wolf" tendencies and have adopted a social existence. Why? Because in certain circumstances, working together is better than working alone. Amazing facts about Social Spiders First, let's figure out how social spiders are different from social insects. We're all familiar with social insects like bees, wasps, and termites, which live in complex societies. These social insects often have distinct castes—each caste with distinct jobs, such as collecting food, or caring for the eggs and young, or defending the colony. There is even a queen, whose sole purpose is to lay eggs. These insects even go so far as to have different biological bodies for the members of each caste, and only a few of them ever have the opportunity to reproduce. Social spiders, on the other hand, do not have these distinct castes, and they do not have different biological body types. Every spider in a colony looks pretty much the same as all the others. Every spider can potentially reproduce. So, why do these spiders live in colonies instead of alone? What is the benefit of living in a group? Keep in mind that, when it comes to questions like these, it's all about mathematics. For example, one hypothesis is that living in a colony results in capturing, on average, more prey per spider. If each spider gets more food, then it is in the spiders' best interest to live in colonies. If each spider gets less food, then it is in the spiders' best interest to live alone. As it turns out, in certain circumstances, spider colonies work better than living alone. In certain circumstances, working together to build a much larger web results in more prey per spider. Amazingly, some social spiders make webs that are 25 feet (7.6 m) tall. Also, in certain circumstances, it is better to have large numbers of spiders to subdue and kill larger prey. While some social spiders live in group of only a few dozen, others live in groups of up to 50,000! Notice that I said this is beneficial in certain circumstances. Let's figure out what these certain circumstances are. First, it is thought that living in colonies helps if the average size of the prey animals in the area is unusually large. After all, it takes a lot of spiders to subdue a bat, a bird, or a large insect. In tropical areas, there are a lot of birds and bats, and a lot of jumbo insects. This is probably why most social spiders tend to live in tropical areas. Here's another idea—living in colonies helps if it rains a lot. Why? Because rain tends to destroy spider webs, and therefore the webs require more maintenance. More spiders equals more hands (or legs) to help out. Social spiders work together to build, maintain, and clean the massive web. Social spiders live mostly in areas that get a lot of rain. Then, of course, there is the actual size of the web. The larger the web, the more insects and other prey it will catch. In order for a 25-foot web to catch enough prey to support thousands of spiders, it must exist in an area that has a lot of insects. You guessed it... tropical areas. Check out this video of a social spider web. And then there is the obvious benefit of defending against predators. Let's say you are looking for a nice spider lunch. If you find a single spider, its pretty easy to snatch it and gobble it up. But if you find an entire army of thousands of social spiders, that's an entirely different challenge. In fact, you might end up being lunch for the spiders! Remember, social spiders are not like social insects. Let's look at how a social spider colony works. Instead of having well-defined castes, social spiders are more egalitarian. All spiders can do all things, and they are all capable of reproducing. The roles in spider colonies are more related to age and gender. And, believe it or not, scientists are starting to discover that these spiders sort themselves by "personality." Certain spiders are more likely to spend their time attacking predators, for example. Certain spiders are more likely to repair the webs, while others are more likely to take care of the colony's babies (each colony has a spider nursery). Astoundingly, more and more studies are showing that these roles are more likely due to individual spider personalities than to genetics. In other words, they actually choose what they want to do with their time! The social spider below, for example, which is battling an invading ant, probably has a more aggressive personality. Even though social spiders can be very successful, this lifestyle is quite rare among spiders. There are about 45,000 spider species world-wide, but only about 25 of those are social spiders. One last interesting tidbit. In 2013, in Santo Antonio da Platina, Brazil, a strong wind storm destroyed many of the area's social spider nests, tearing portions or entire nests free and hurling them into the air. This event led to a “spider rain” in which people in Santo Antonio da Platina observed spiders raining from the sky. So, Social Spiders deserve a place in the P.A.H.O.F. (Phat Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word phat may have originated in the early 1980s. It is thought to have started as hip-hop slang, meaning "great or excellent." It is presumably an intentional misspelling of the word fat, kind of like the word boyz. In this case, fat is being used the way it has for centuries, as slang meaning ''rich,'' as in ''fat and happy." I will point out that some people think the word phat started out with a meaning related to admiration of a woman's form (such as, pretty hips and thighs). But... this is considered incorrect, and it is assumed that this meaning may have originated as an improvised explanation to women who felt insulted by the word. Regardless, it is mostly used to mean "great or excellent," and therefore phat is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Social spiders attacking wasp - Reddit Social spider web #1 - UnbelievableFacts Large social spider colony - turdusprosopis on Flickr Social spiders eating grasshopper - ThinkJungle Social spider battling an ant - Graham Montgomery via Earth.com

0 Comments

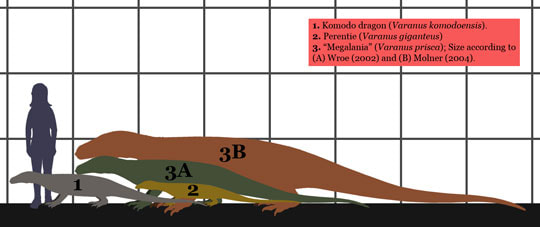

My novella, FUSED: TRAINING DAY, features several fascinating creatures. The most bizarre of these happens to be an extinct lizard. It's not really an animal you want to have in your living room. Way back in 1995, when Trish and I were on our first trip to Australia, we visited a natural history museum in Brisbane. There was a dark display hall with a carefully-reconstructed primeval forest. The star of the show in that forest (in my opinion) was a model of a massive monitor lizard called a megalania. That creature has stuck in my mind ever since, and I have always known I would find a way to have one show up in one of my stories. So, since I just released FUSED: TRAINING DAY, this is also the perfect time to feature the megalania as an Awesome Animal! What the heck is a Megalania? During the Pleistocene (2.5 million years to about 12,000 years ago), fierce mammal predators, such a saber-toothed cats, ruled most of the world. But not so much in Australia. The apex predators in Australia were reptiles, including land-dwelling crocodiles, enormous snakes, and huge monitor lizards. The megalania was the largest of these monitor lizards. The megalania (Megalania prisca or Varanus priscus) lived from about 1.6 million years ago to about 40,000 years ago. It is also called the giant goanna (goanna is the name given to certain monitor lizards, particularly in Australia). Amazing facts about the megalania Okay, the first thing we need to do is figure out exactly how big these things were. The megalania is touted as the largest terrestrial lizard to have ever roamed the earth. Is this true? The largest living lizard is the Komodo monitor (the Komodo dragon), which can grow to be 10 feet (3 m) long and weigh 150 pounds (70 kg). We'll use the Komodo as a standard for comparison. The strange thing is, the assumed size of the megalania has changed greatly based upon different studies that have been done. Why? because complete fossil skeletons are rare. The earliest estimates put megalanias at about 23 feet (7 m) long and about 1370 pounds (620 kg). In 2009, the megalania was downgraded to 18 feet (5.5 m) and 1,268 pounds (575 kg). The author of the study argued that the previous estimates used flawed methods. However, in a completely different study published in 2004, Ralph Molnar did a very comprehensive study comparing fossil megalania bones to the bones of two different living monitor lizards. One was the lace monitor, which is long and thin, and the other was the Komodo monitor, which has a thicker body. The conclusion? If the megalania was shaped more like the lace monitor, it was 26 feet (7.9 m) long. If the megalania was shaped more like the Komodo monitor, it was 23 feet (7 m) long. The largest individuals would have weighed 4.280 pounds (1,940 kg)! Yeah... I know what you're thinking. What difference does it make, right? Whether it's 1,200 pounds or 4,200 pounds, this was a big honkin' lizard—way, way bigger than a Komodo dragon. In the diagram below, 3A is the small estimate, 3B is the large estimate. Lizard 1 is the Komodo dragon (the largest lizard living today). It's important to remember that we aren't talking about a dinosaur. Dinosaur skeletons were structured very differently from lizard skeletons. Dinosaurs had legs positioned directly beneath their bodies, able to support vast amounts of weight. Lizards, though, have legs that extend out to the sides. With no direct support from underneath, lizards simply cannot grow all that large. Most lizards are the size of your hand or smaller. Many are smaller than your pinky finger. So, the megalania was a big lizard. If you saw a 4,000-pound predatory lizard coming your way, you would probably want to make yourself scarce. As if the size wasn't intimidating enough, these lizards were probably venomous. You read that right. The megalania belongs in a reptile group (specifically, a clade) called Toxicofera, which includes all the reptiles that have venom-producing glands in their mouths. Here's how this venom works (based on what we know about living monitor lizards with venom, such as the Komodo dragon). The vemon, produced in the lizard's jaw, is a hemotoxin. This means it attacks the blood. Specifically, it prevents the blood from clotting. So... the lizard bites the heck out of its prey (Komodo dragons have a seriously nasty bite), the prey starts to bleed, and the hemotoxin greatly increases the bleeding. Soon, the prey animal goes into shock and collapses. Then... lizard lunch! Because of the megalania's hemotoxic venom, these lizards were probably capable of taking down very large prey. The painting below shows a megalania stalking a herd of huge herbivorous marsupials. Check out this video about the megalania (kind of long but informative). Below are two Komodo monitors fighting. They are each probably about 7 feet (2.1 m) long. Now, picture what this would look like of they were each 23 feet (7 m) long! Several hypotheses have been formed to explain the extinction of megalanias, which happened about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago. First, some people suggest they went extinct after several large prey species went extinct, specifically Diprotodon and Procoptodon. When these animals disappeared, there was simply not enough food to support a population of such large lizards. Second, some people think the first humans to colonize Australia may have hunted megalanias to extinction (try to imagine hunting an adult megalania with primitive weapons!). This hypothesis is supported by the fact that humans entered Australia at about that time. Third, it seems likely that their extinction was caused by a combination of #1 and #2 above. Perhaps humans burned huge swaths of forest, and in doing so they killed off the food supply for megalania prey species. And... fourth, some people like to believe that megalanias are still alive, with isolated populations hidden in remote areas of Australia. There have been stories of large footprints found, cattle killed with suspicious bite marks, and so on. BUT... as cool as it would be to find living megalanias, the possibility is HIGHLY UNLIKELY. So, the Megalania deserve a place in the P.K.A.H.O.F. (Peachy Keen Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The adjective phrase peachy keen was popularized (and probably invented) by a Los Angeles DJ named Jim Hawthorne around 1948. The young DJ, it seems, was bored with his job. One night, without notifying his bosses, Hawthorne turned his show into a wild, carefree program he referred to as "Hellzapoppin on the air." Before the station could fire him, they were inundated with fan mail. The program soon exploded in popularity. One of Hawthorne's signature phrases was "Oh so peachy keen." Well, the phrase is still being used, and it means excellent, wonderful, and fine. So, peachy keen is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Megalania #1 - Dinosaur Park Size diagram - Wikimedia Commons Fighting Komodo monitors - DepositPhotos Megalania stalking marsupials - Laurie Beirne via Science Magazine Megalania pursuing a Bullockornis - Peter Trusler, via Monash University on Flickr via NatGeo |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed