|

For those not familiar with January in Missouri (central US), I'll describe it. January is perhaps the coldest month of the year here. The trees are bare and the ground vegetation is brown and dead. There are no insects around, so those animals that eat insects (at least those that live above ground) must hibernate or migrate. Most of the nights are below freezing, and it can get to -10 F (-23 C). But that doesn't mean we don't have the odd warm day. Trish and I just got back from several relaxing days at our rustic little cabin in the Missouri Ozarks. On Sunday, the temperature hit 71 F (22 C). This happens occasionally. But amazingly, in the afternoon the woods behind our cabin suddenly filled with the beautiful calls of the tiny frog called the spring peeper! Some of you in warmer areas may hear frogs all year around, but hearing them here in January is a real treat. So to celebrate this event, I have chosen the spring peeper as the Awesome Animal for this post. Here's what the forest behind our cabin typically looks like in January. This was January 19th, from a trail camera we've installed to get photos of wildlife (this lovely picture of the snowy forest was photo-bombed by a white-tailed deer). Often I feature animals that show up in my novels, but not this time. This email is in honor of those brave little frogs that dared to awaken and begin calling on January 21st in the Missouri woodlands. So what the heck is a Spring Peeper? Spring peepers are frogs, so they are in the class Amphibia (amphibians). Their scientific name is Pseudacris crucifer. The second part of the name comes from the fact that they have a distinct X (cross) on their back. They live in the eastern half of North America, including eastern Canada. Spring peepers are only about one inch long, but their call is extremely loud for such a tiny critter. They are usually the first frog to become active and start calling in early spring, so their call is a welcome sound to many people. Amazing facts about Spring Peepers So, why would Trish and I hear spring peepers in mid-January? To understand this, it is important to know how frogs spend their winters. Amphibians have porous skin, and oxygen can pass through it. When winter approaches, frogs simply swim to the bottom of a pond and wriggle back and forth until they are partially or completely under the mud (some of them crawl into the mud beneath rotting logs). When the temperature drops, their metabolism slows down enough that their skin can absorb adequate oxygen from the surrounding water. If the temperature gets too warm, their metabolism increases and their skin cannot take in enough oxygen to sustain them, so they have to swim to the surface to breathe with their lungs. So on January 21st, when the temperature rose to 71 F, the ice thawed out and the water warmed up enough that the spring peepers were forced to emerge to the surface. And if you're a male spring peeper, when you get to the surface, you have this uncontrollable urge to call for a mate. And that's why Trish and I were treated to a symphony of horny frogs in the middle of winter! Check out this video of spring peepers calling. If these frogs choose to spend their winter at the bottom of a rather shallow pond, that pond may freeze completely. Well, not to worry. Spring peepers are one of only five frogs in North America that can survive being frozen. When the temperature of the water or mud around them drops below freezing, their body starts producing a natural antifreeze, which protects their most vital organs. But 70% of their body freezes solid! Their heart even stops beating, and they appear to be dead. We still don't completely understand how these frozen frogs are able to come back to life. They are tough little frogs! Spring peepers have an impressive vocal sac.The vocal sac is that bulging throat you see under the chin of many male frogs. It's a flexible membrane that amplifies the sound of the male frog's call. The vocal sac, in fact, is one reliable way to tell the difference between males and females of many frog species. There are two slits in the bottom of the male's mouth connecting the mouth to the vocal sac. The frog fills its lungs with air, closes its nose and mouth, and blows the air through its vocal chord (larynx), producing its call. The louder the call, the better, because the nearest female may be way over in the next pond. Although spring peepers are a type of chorus frog, they have something in common with tree frogs: sticky toe pads that allow them to cling to leaves and other surfaces. They can climb vertical surfaces and even cling to leaves upside down. A study in 2009 revealed how frog toe pads work. If you look very closely, the toe pad surface is covered with flat-topped cells surrounded by grooves filled with mucus. But when scientists looked even closer at those flat-topped cells with a special super-duper microscope (called an atomic force microscope), they saw that they were covered with jillions of tiny "nanopillars." With all these nanopillars, a huge amount of surface area comes in contact with the climbing surface, and the mucus helps to provide adhesive forces. It's an amazing adaptation. Like many other frogs, spring peepers take the shotgun approach to breeding. Since most of their young are eaten by other predators in the water, they lay about 900 eggs! This makes it more likely a few of them will survive. In the spring, when a male successfully calls a female to him, he will climb onto her back and hold on tight (this is called amplexus) until she lays her eggs (eggs are layed in the water). Amplexus puts the male in a good position to release sperm onto the eggs as they come out of the female's body. By the way, this amplexus is such a powerful instinct in male frogs that I have seen triple-decker amplexus before (where a second male clings to the back of a male that is clinging to the back of a female, perhaps in hopes of getting his sperm onto some of the eggs). As you can imagine, since spring peepers are small, and they lay 900 eggs, the resulting tadpoles are really small: So, the spring peeper deserves a place in the O.F.A.H.O.F. (On-Fleek Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: On fleek is a relatively new term (used by people much younger than me). It's an adjective to describe something that is so good that it's "on point." It originated as a reference to eyebrows (eyebrows waxed to perfection are "on fleek"), but now can be used to describe just about anything that is outstanding. So it is another way to say awesome. Photo Credits:

Spring Peeper on finger - Little Peppers Field Guide Spring Peeper Vocal Sac - Farmer's Almanac Spring Peeper Toe Pads - Hilton Pond Center Spring Peeper in Snow - Naturally Curious with Mary Holland Spring Peeper Tadpole - Capital Naturalist

0 Comments

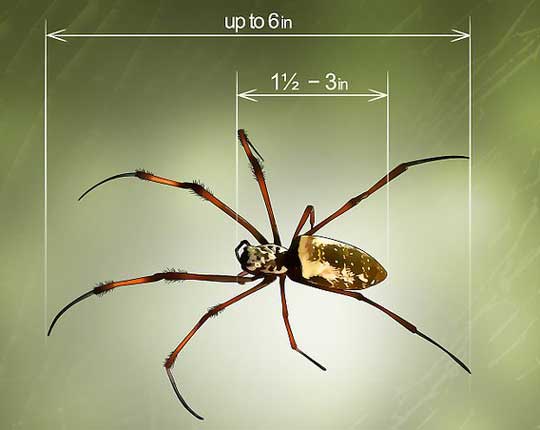

I enjoy featuring animals that show up in my novels. In Diffusion, there is a scene where Samual shows Quentin one of the huge orb-weaving spiders that produce the silk the Papuan natives use to make incredibly strong rope. As it turns out, the spider in my story is not as exaggerated as you might think. Today's awesome animal is the orb-weaving spider, especially the giant golden orb-weaver. So what the heck is an Orb-Weaving Spider? Orb-weavers are a large family of spiders that include over 3,100 species. These are the spiders that typically build large, spiral webs in your garden. Their webs are typically wheel-shaped, and that's how they got the name of orb-weavers (orb general means circular). I am going to focus mainly on the golden orb-weavers (spiders of the genus Nephila). Why? Because they are some of the largest and most beautiful spiders. Below is a photo of a golden orb weaver Trish and I encountered on a hike in Costa Rica: Amazing facts about Orb-Weaving Spiders Some orb-weavers are quite large. The females of the giant golden orb-weaver can have a body length of up to 3 inches (75 mm), and with the long legs included, a entire length of 6 inches (150 mm). But the most striking thing about their size is that the females are HUGE compared to the males. When the male and female of a species are different from each other, it is called sexual dimorphism. But orb-weaving spiders have taken the concept of sexual dimorphism to the extreme. The females can be up to TEN times longer than the males. And this means the male weighs less than 5% of the weight of the female. Wow! Just for kicks, let's convert that to human terms. Let's say there is a 140-pound woman. Her mate would be a man who weighs less than SEVEN pounds. Okay, that's just a little weird to think about. Check out this video of a male and a female golden orb-weaver. There are two main theories for why they are so different in size: Theory #1: In many spiders, once the male mates with the female, he inserts a "mating plug" in the female, which prevents other males from mating with her (I am not making this up!). By doing this, the male can be sure he is the father of all the offspring of that female. But in giant orb-weavers, these plugs do not seem to work. And so the theory is that the females of these species have evolved to be very large so that they can be too large for the plugs to work, thus ensuring that they can produce young from more than one male (more diverse offspring, which is a good thing from the female's perpective). Theory #2: In giant orb-weavers, the males that find and mate with a specific female first will fertilize more of her eggs than males that find her later. And smaller males are faster, so they can scramble around through the vegetation and find females faster than larger males. And thus the males have evolved to have a smaller size. Again, I'm not making this stuff up. See the male and female in the photo below. Well, as you can imagine, for a tiny male orb-weaver, mating with a giant female is risky business. The females have a habit of eating the males after the "job" is complete. But some male orb-weavers have a special strategy to avoid this. It's called mate-binding. To make the females more receptive (and less likely to cannibalize them), the males spread silk over the female's back, in a motion that looks very much like he is giving her a massage. Research shows that this massaging motion makes the female relax, and therefore she is less likely to eat the male. Here is a video of mate binding in orb weavers. Although most orb-weavers are fairly docile, they can certainly bite. But they are not dangerous to humans. They inject neurotoxin, like a black widow spider, but it is much less toxic. As I mentioned earlier, in my Diffusion novels orb-weaver silk is used to make very strong rope. This is actually possible, assuming there is a good way to harvest lots of spider silk, because orb-weaver silk is strong! In fact, it's the strongest biological material we know of. It is more than ten times stronger than a strand of Kevlar of the same diameter. The recently-discovered Darwin's Bark Spider, a type of orb-weaver, has the strongest silk of any spider. They create webs that are more than 80 feet (25 meters) wide! The actual circular part of the web (the part that catches insects and other small animals) can be a meter in diameter. See the Darwin's bark spider web below. In Diffusion, Samuel Inwood made his vest from orb-weaver silk. Actually, few people have been able to do this, as spider silk is not easy to collect in large amounts. In 2012, a textile designer and an entrepreneur collected golden orb-weavers from the wild and managed to get enough silk to create a beautiful cape, which was put on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (see photo below). It took over three years to make! So, the orb-weaving spider deserves a place in the H.S.A.H.O.F. (Heart-Stopping Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The first-known use of the phrase heart-stopping was in 1888. It is possible that it started as a reference to the (incorrect) assumption people used to have that one's heart would stop when sneezing. Today it refers to anything that is so frightening or emotionally gripping as to make one's heart seem to stop beating. I like to use it in a positive way, though, to describe something amazing or exciting. So it is another way to say awesome. Photo Credits: Golden Orb-Weaver on fingers - Stan C. Smith Golden Orb-Weaver Size Diagram - WikiHow Male and Female Orb-Weavers - National Geographic Darwin's Bark Spider Web - Wikimedia Commons Orb-weaver Silk Cape - Wikimedia Commons |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed