|

In 1995, Trish and I were lucky enough to tour a fascinating cave in New Zealand. As we came out of the cave, there was a funny-looking bird sitting on a handrail within arm's reach of me. The bird simply stared, with no apparent urge to fly away. It had a cartoon-like face and a wide mouth that reminded me of a frog's mouth. In fact, this bird was actually a tawny frogmouth. What the heck is a Frogmouth? First of all, despite their owl-like appearance, frogmouths are not owls. They are actually related to nightjars (the nightjars are insect-eating birds with short, broad beaks... in Missouri we have three nightjars, the nighthawk, the whip-poor-will, and the chuck-will's-widow). However, frogmouths are often mistaken for owls because they are nocturnal and their feather coloration is similar to some owls. This similar appearance is a great example of convergent evolution, in which unrelated organisms evolve to look similar to each other because they are adapted to similar habitats and habits. Owls and frogmouths both hunt at night, so they both have large eyes and similar camouflage patterns. However, frogmouths do not have strong claws like owls. Owls use their claws to hunt larger prey, whereas frogmouths catch insects and small vertebrates with their mouths instead of their talons. They can open their mouths wide to scoop up flying insects. Frogmouths live across much of Southeast Asia and Australia. There are 14 species of frogmouths, but the tawny frogmouth is arguably the best known of all of them. Well, at least it's the one most frequently seen on the internet. In fact, in April 2021, German researchers did a study using an algorithm to analyze the aesthetic appeal of over 27,000 bird photos and found that Instagram users "liked" frogmouth photos more than any other bird photos. Therefore, frogmouths are officially the world's most Instagrammable bird species. Amazing Facts about Frogmouths First, I recommend that you watch this fun video about frogmouths. It's worth the five minutes of your life that it will take to watch it. Okay, if you watched the video, you probably want to know more, right? Like, did he say frogmouths bash their prey against rocks? He did indeed. Remember, owls have strong claws for killing, frogmouths don't (their feet are small and rather weak). Instead, they have... well, big mouths. They can grab prey animals that are bigger than insects (frogs, reptiles, small birds and mammals), but instead of tearing them apart with talons, they whip them against a rock or tree over and over. Then they swallow the bashed-up creature in one gulp. That's dramatic, I suppose, but the majority of a frogmouth's diet is smaller critters—nocturnal insects, slugs, snails, and worms. Most of these they see from their perch in a tree and pounce onto them on the ground. Sometimes they catch insects in flight, which unfortunately leads to these birds being hit by cars while swooping in to catch insects attracted to bright headlights. Frogmouths are really good at camouflage. You can see from the photo above that their color allows them to blend in, but that's just the beginning. When they sense danger, they get into a position that makes them look like a broken branch on the tree. Sometimes they will even sway back and forth as if the wind is blowing the tree. Frogmouths actually seek out old trees to sit in because it's easier for them to look like an old, stumpy tree limb. Below is a Javan frogmouth on its nest, trying to look invisible. I guess we need to talk about the pitiful nests these birds create (see photo above). When it comes to nest-making, frogmouths definitely would not win the Engineer-Of-The-Year award. Their nests are rather minimalistic. Sometimes they lay their eggs in the fork of a tree with hardly any nest at all. Sometimes they place a few sticks together and call it a nest. Or they use a bit of moss, lichens, or leaves. These nests are well camouflaged, but they don't do much to keep the eggs from falling out of the tree, which definitely happens sometimes. Well, perhaps they don't make the most impressive nests, but that's not to say they don't excel in other aspects of parenting. Frogmouths are excellent at sharing the duties. They are known to mate for life, and both sexes sit on the eggs—the male sits on the nest all day long, but then the male and female take turns during the night so they can both go out hunting for food. So, even though the nest is wimpy, the eggs and young are almost never left unattended. Both parents work hard to provide food for the growing chicks. Below is a Hodgson frogmouth sitting on its nest with two chicks. I can't decide if those chicks are cute or scary-looking. Frogmouths have a strange call. Sometimes they hiss or growl if they feel threatened, but their usual call is a low, monotonous wooo-wooo-wooo. Check out this video (you need to listen carefully... you can hear it in the last half). Frogmouths are good at surviving extreme temperatures. When temps get really low and food becomes scarce, frogmouths are able to go into a dormant state called torpor. This drastically lowers their heart rate, metabolic rate, and temperature, which therefore reduces their need for food. Torpor is not the same as hibernation. Hibernation is a long-term state, whereas torpor is usually only a few hours at a time. Still, frogmouths can go into torpor repeatedly, spending much of the days and nights of the cold season in a low-energy state. In the hot months, frogmouths open their mouths and pant. The moving air helps cool them down. To increase the effectiveness of this, they fill their mouths with mucus, which helps cool the air as it is inhaled. I mentioned above that frogmouths often mate for life. Continuous close proximity and physical touch seem to be important ways for frogmouth pairs to reinforce their bond (Hey, I can identify with that!). Pairs typically spend their down time sitting beside each other, even close enough that they are touching. A male often grooms the female's feathers, sometimes doing this for up to ten minutes without stopping. Below is a bonding pair of Sri Lanka frogmouths. So, the Frogmouth deserves a place in the P.A.H.O.F. (Portentous Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word portentous originated way back in the 1540s. In fact, it was seemingly a favorite word of William Shakespeare. It came from the Latin word portentosus. The root of the word, portent, was a synonym of a sign or an omen. When the word portentous was first used, it was always in reference to an omen, usually a bad omen. However, by the end of the 1500s, the word began being used as a synonym for prodigious, which means "remarkable or impressively great in extent, size, or degree." Today, many years later, the word is often used to mean "trying to appear important and serious." Well, take one look at the frogmouth and you'll agree this definition fits. Frogmouths look very important and serious to me. So, more or less, portentous is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Tawny frogmouth #1 - DepositPhotos Two tawny frogmouths on opposite sides of tree trunk - Keith Edkins, Wikimedia Commons Javan frogmouth on nest - camouflage - DepositPhotos Hodgson frogmouth with two chicks in nest - DepositPhotos Pair of Sri Lanka frogmouths - DepositPhotos

1 Comment

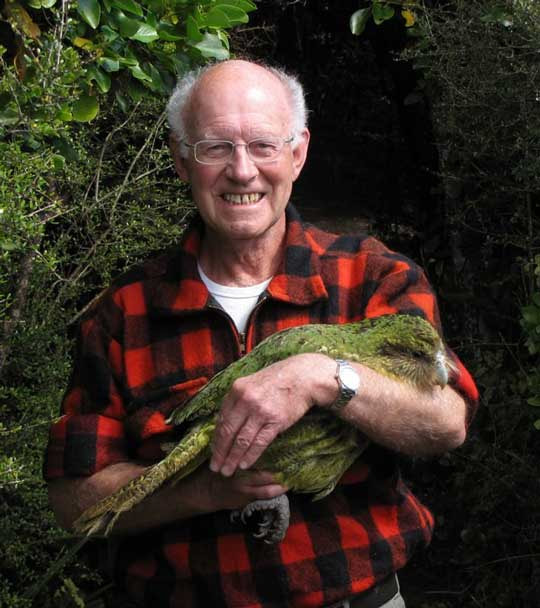

Way back in 1758 Carl Linnaeus described a type of lizard that had strange flaps of skin on its sides that looked almost like wings. He named the genus Draco, which is from the Latin word for dragons... you know, those giant, mythical flying reptiles. Back then, scientists did not know if the wing-like flaps of skin were actually for flying. In fact, this possibility was debated all the way into the mid 1950s. Many scientists thought the flaps were used only for threat displays or mating displays. Finally, in the 1950s, scientists actually observed the lizards gliding from tree to tree on these flaps of skin. What the heck is a Flying Dragon? Normally I share a YouTube video closer to the end of the Awesome Animal feature, but in this case I think you need to see the video first, in order to fully appreciate the awesomeness of these lizards before I go into more detail. Check out this must-see video from the BBC. See what I mean? Impressive lizards! There are actually about forty species of Draco flying dragons, and they live in dense forests in Bornea, the Philippines, and across southeast Asia into southern India. They are fairly small lizards, averaging about 8 inches (20 cm) in length, including the tail, and they are all insectivores, gobbling up numerous insects per day. Typically, they are drab in color, but their wing-like membranes, called patagia, can be brightly colored. Amazing Facts about Flying Dragons First, we need to talk about this whole flying thing. What the heck—a flying lizard? Not exactly. When it comes to animals, the word flying usually refers to the animal's ability to propel itself through the air under its own power for a sustained period of time. Birds, bats, and many insects can actually fly. Pterosaurs were real flying reptiles, and they could flap their wings for sustained flight, but they went extinct about 66 million years ago. Draco flying dragons are not miniature pterosaurs, and they cannot fly. Instead, they are lizards, and they glide instead of fly (kind of like flying squirrels, which I featured in a recent email). Don't let that fool you, though! Draco lizards are really good at gliding. They sail through the air with precision control, and people have observed them gliding as far as 200 feet (60 m) between trees. Look out your window at a tree that is 200 feet away. That gives you an idea of how impressive this feat is. By the way... look at the lizard on the right (on the tree) in the photo above. That is what they look like when their wings are not spread out—pretty much like a normal lizard. How exactly do Draco lizards glide? That impressive patagial membrane (wing) is supported by special, elongated rib bones, which the lizard can spread wide after it takes to the air, using certain muscles that other lizards usually use to control their breathing. The lizard leaps from a tree and spreads its ribs, which spreads the patagial membranes on both sides of its body. It then grabs the membranes with its forefeet to hold them out, then arches its back to force the wings into a concave shape, which enhances lift. The lizard controls its flight path by moving the wings up and down with its forelimbs. Check out those elongated ribs! Okay, that makes sense. Now, WHY do Draco lizards glide? Remember, lizards are gobbled up by numerous predators. Walking around on the ground to get from tree to tree is dangerous business. So, there is a huge advantage to being able to glide between trees. Maybe a better question is, why don't all lizards glide? There are many different answers. Not all lizards are small enough to glide. Not all lizards live in densely-forested areas (no point in gliding in a desert or grassland, right?). And there are numerous other reasons why not all lizards can glide. The question is kind of like asking, if gliding is good for Draco lizards, why can't people glide too? In the past there have been other lizard species (now extinct) that have independently evolved this same ability. For example, there was a family of gliding lizards called Kuehneosauridae that lived during the Triassic period (251 to 201 million years ago). Their fossils show a similar structure to today's Draco lizards (see artist depiction below). Male flying dragons also use their "wings" as displays to impress females. This is probably why some of them have brightly-colored patagia. In addition to their patagia, the males also have dewlaps, colorful folds of skin beneath the chin that males can extend to further add to their impressiveness (see below). The males establish territories and guard them fiercely to keep other males out. Of course, the females are always welcome, and they move from territory to territory, checking out the males to see which one they are most impressed with. So, the Flying Dragon deserves a place in the C.A.H.O.F. (Choice Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word choice originated as a noun in about 1300. It came from the earlier French word chois, and its original meaning was "action of selecting" or "power of choosing" (as in, "I have no choice—I must read Stan's new book"). In the late 1300s, the word was also used as a noun for "the person or thing chosen" (as in, "Stan's new book is going to be my next choice"). Sometime in the mid 1300s, people began using the word as an adjective to mean "worthy of being chosen; excellent; superior" (as in, "Stan's new book will be one of the choice novels of our generation"). So, choice is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits: Flying dragon gliding #1 - Psumuseum, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Flying dragon on tree with yellow patagia spread open - A.S.Kono, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Flying dragon landing on a tree - DepositPhotos Flying dragon skeleton diagram - Wikimedia Commons Prehistoric gliding lizard art - Nobu Tamura (http://spinops.blogspot.com), CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Draco volans displaying with dewlap - DepositPhotos Thanks to reader (also one of my former 7th grade life science students) Scott Finley for suggesting this Awesome Animal. Way back in 1995, Trish and I had a marvelous opportunity to travel to New Zealand. At a zoo there, we had our first introduction to the weird and wonderful kakapo (pronounced KAH-ke-poh), which is perhaps the most unusual of all parrots. These large parrots displayed endearing personalities, and we were immediately enamored by their appearance and antics. I think you'll find them just as fascinating as we do. What the heck is a Kakapo? For one thing, the kakapo is nocturnal—the only nocturnal parrot. And it is flightless—the only flightless parrot. Kakapos are massive, nine-pound parrots—the world's heaviest parrot. They spend their nights waddling around on the forest floor and climbing trees to find their favorite fruits and seeds. To top it all off, the kakapo might be the world's longest-living bird, with some individuals living up to 100 years. Kakapos are endemic to New Zealand, and unfortunately they are highly endangered. In fact, I suppose Trish and I were lucky to see them at all—when we were there in the mid 90s, only 51 individual kakapos remained. The number is now closer to 200, which is good, but the species' survival is still far from assured. The photo below gives you an idea of the kakapo's size. Amazing Facts about the Kakapo A flightless parrot? Really? Yep, completely flightless. Although this is the only flightless parrot, other birds have also evolved to be flightless on oceanic islands where there are few predators. Historically, New Zealand had no large land predators, resulting in a variety of flightless birds that would otherwise be vulnerable, such as the kakapo, several species of kiwi, three species of penguins, the takahe, the weka, and several species of flightless teal (teal are a kind of duck). In addition, New Zealand was home to a variety of extinct flightless birds, including the huge, impressive moas, which were the tallest birds known, able to reach foliage 12 feet (3.6 meters) off the ground. I guess you could say New Zealand is the flightless bird capital of the world. Before humans arrived on New Zealand, the only predators kakapos had to worry about were birds of prey: one species of eagle, one falcon, one harrier, and one owl. Over time, the kakapo became well adapted to avoid these raptors—the parrots developed camouflaged feathers and became nocturnal. When kakapos feel threatened, they freeze, which helps them blend in with their surroundings. Although the eagle, falcon, and harrier only hunt in daylight, the nocturnal laughing owl could still sometimes prey on kakapos. However, the real problems started when humans brought predatory mammals to New Zealand, particularly dogs, cats, and stoats (the short-tailed weasel). Part of the problem is that a kakapo's body has a strong, musty-sweet smell (they use this smell to locate each other). This was not a problem when raptors were their only predators—raptors hunt by sight, not by smell. Mammal predators, on the other hand, have a highly developed sense of smell. Not a good thing for the kakapos! With mammals hunting them, the kakapo's tendency to freeze does not help at all and in fact makes them easy prey. The Polynesian ancestors of the Māori (indigenous people of mainland New Zealand) arrived in New Zealand about 700 years ago, and they brought with them domesticated dogs called Kurī (a now-extinct breed of Polynesian dogs). The Māori used these dogs as a source of food, but they also used them to hunt birds, including the kakapo. Also, the Māori inadvertently brought rats (as stowaways on their boats) to New Zealand, and the rats proliferated and preyed on kakapo eggs and chicks. By the time Europeans arrived in 1642, the Māori had decimated the kakapo in some parts of New Zealand. Then, as I'm sure you can guess, the Europeans greatly accelerated the kakapo's decline. Not only did they clear vast tracts of land, they brought additional mammals, including different dogs, domestic cats, black rats, and stoats. By the late 1800s, the kakapo was recognized as a scientific curiosity, and thousands of them were killed and shipped to numerous museums around the world. As I said above, when Trish and I saw these birds in a New Zealand zoo in 1995, there were only 51 individuals known to exist. Soon after that, all the remaining kakapos were transferred to four islands that had been cleared of all non-native predators and competitors, and were also replanted with native vegetation. Additional ongoing eradication efforts have been because cats, stoats, and rats continually reappear on the islands. These protected kakapos have gradually increased to about 200 birds. Below is a Department of Conservation worker caring for some kakapo chicks. Check out this video about the kakapo. If you watched the video linked above, you saw a kakapo running toward the camera man, then stopping to take a closer look. Kakapos are notoriously friendly birds, and even those living wild on the protected islands are known to come right up to people, climb all over them, and even preen their hair. Of course, this friendly behavior has contributed to their decline, as they are extremely easy for humans and predators to hunt. In addition to hunting and eating kapakos, both the Māori and early European settlers kept these birds as pets. Let's finish this up with a bit about the kakapo's sex life, which is just as unusual as all their other characteristics. Kakapos are the only parrots to have a a polygynous lek breeding system. That's a mouthful, so let's break it down. Polygynous means that one male mates with numerous females, but those females only mate with the one male. A lek is when a group of males gather in one area to compete for females by carrying out elaborate displays and behaviors. Females pick out their preferred males as the males display, or lek. Amazingly, mating occurs only once every five years! This coincides with the ripening of a specific type of conifer seed called the rimu fruit, which kakapos love to eat. When it is finally time, the males will walk (remember, they can't fly!) up to four miles (6.4 km) to get to the lekking arena. At the arena, before the females arrive, the males fight aggressively for the best locations within the arena (each location is called a court). The most dominant males get the best courts. Each court is a bowl-shaped depression in the ground, previously dug by male kakapos. The court bowls are usually situated near large rocks, a dirt bank, or tree roots that act to amplify sound. Why? Because the male kakapos make a lot of noise to impress the females. In fact, males make a loud booming sound all night long (about 8 hours non-stop), every night for a four-month period of time! The booms can be heard up to 3.1 miles (5 kilometers) away. This is such exhausting work that the males often loose 50% of their body weight during these four months (now you see why they only do this when abundant rimu fruits are ripe). As you can imagine, this booming activity can attract non-native predators from a long distance. Darn those non-native predators! Once a female approaches a male's court, he performs an elaborate dance to impress her. Once they mate, the female heads back to her own territory, and the male keeps right on booming, hoping to mate with as many additional females as possible. Females don't even reach sexual maturity until about nine years of age, and they only breed once every five years, so the kakapo is one of the slowest-breeding birds. This is why conservation efforts to increase the population have been so slow. Below is a kakapo chick. So, the Kakapo deserves a place in the N.A.H.O.F. (Neat Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word neat originated in the 1540s, and it meant "clean, free from dirt." Originally it came from the Latin nitidus, with the literal meaning "gleaming." In the 1570s, it took on the meaning "inclined to be tidy," and in the 1590s the meaning "in good order." In about 1800, it began to be used to describe liquor that was "straight, undiluted." Finally, starting in 1934, neat was being used to mean "very good, desirable." The slang variant "neato" appeared in the 1960s. Today, neat is often used as a whimsically outdated adjective (see the silly "neature walk" videos). How neat is that? That's pretty neat! So, neat is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Kakapo on ground - "Kenneth' Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Kakapo held by man - Errol Nye, National Kakapo Team, DOC. [email protected] by Ppgardne at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Kakapo hiding on the ground - "Hugh' Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Kakapo chicks being fed - Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons Kakapo chick - "K1', Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed