|

The pangolin is a strange mammal. Considering how bizarre it is, you'd think it would be more widely recognized. But I've discovered many people have never seen a picture of one, and even fewer would recognize the name Pangolin. I'm a sucker for the really weird creatures, so I'm excited to share this one with you. So, what the heck is a Pangolin? Pronounced pang-guh-lin. Pangolins are also called scaly anteaters. They are mammals in the family, Manidae. There are currently eight species, but we know of a number of extinct species. They are found in some areas of Asia and the southern half of Africa. Pangolins have the distinct honor of being the only mammals with large scales for protection. Amazing facts about the Pangolin So what's up with those scales? A pangolin's scales are made of a protein called keratin, which is the same stuff that makes up human fingernails and hair. Keratin is also what makes up feathers, horns, hooves, and claws. So keratin is useful stuff! Pangolin scales are very different from the scales of reptiles, both in structure and composition. The scales provide protection from predators. When attacked, a pangolin will roll into a ball and tuck its vulnerable head under its heavily-armored tail. In this position, they are nearly indestructible. Not even a lion can chew through the armor! The scales make up about 20% of the animal's body weight. By the way, the underside of a pangolin is not covered in scales. Instead, it is supple skin with a few sparse hairs. So it's a good thing they can roll into a ball. Pangolins have no teeth. Yep, that's right. In this respect, they are like anteaters and armadillos (although they are not closely related to either). Pangolins feed mostly on ants and termites. They have an extremely long, sticky tongue (sixteen inches long, which is sometimes longer than the pangolin's body... wow!), with which they slurp up insects at an amazing rate. They can eat 200 grams of bugs per night, which adds up to 70 million ants and termites per year! Obviously, they are important regulators of ant and termite populations in the areas where they live. Check out this pangolin's tongue: And take a look at this 11-second video of a pangolin sticking its tongue out! The tongue is coated with sticky saliva. A pangolin can shove its tongue deep into the tunnels of ant and termite nests, and when it pulls the tongue back out, it's covered with yummy, juicy bugs. To help pangolins find all these ants and termites, they have long, sharp claws on their front feet for digging into the insects' mounds. They also use their claws to pull the bark from logs and trees to find ants and termites. In fact, they have prehensile tails, and they can hang upside down from a branch as they pull the bark from the tree's trunk. Okay, if pangolins don't have teeth, how do they chew up all those ants and termites? While they are foraging, they swallow small pebbles. These pebbles go into a portion of their stomach called the gizzard. When the insect prey are swallowed and enter the muscular gizzard, the stones chew up the insects before the insects move on to the rest of the stomach. As you may know, birds also have gizzards since they don't have teeth. Pangolins live most of their lives alone, getting together to mate only once per year. Most of the species give birth to only one baby. When the baby is born, its scales are soft (no doubt to make the birth easier on the mother!), but soon they harden and look like those of the adults. As the babies mature, they often ride around on the mother's back or on the top of her tail. Unfortunately, the pangolin has the dubious distinction of being the Most Illegally Traded Mammal In The World. Since 2006, over a million pangolins have been taken from the wild to meet the demand for their scales and their meat (particularly in East Asia and parts of Africa). Their scales are considered essential for making some traditional medicines (but there is no evidence that any part of a pangolin has a beneficial effect on humans), and their meat is considered a delicacy. But... things are looking better. In 2016, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) passed a motion to move pangolins to Appendix I – offering all eight species of pangolin from both Asia and Africa the highest levels of protection, making trade in their parts completely illegal. This, and some aggressive public awareness campaigns should give these unique creature a better chance of surviving extinction. You REALLY need to see this video! This is an ad from WildAid, to help make people aware of the plight of the pangolin and the new regulations banning the trade of pangolin products. It stars the awesome movie star, Jackie Chan. One last tidbit. The third Saturday in February happens to be World Pangolin Day. That's February 16, 2019. This is to make more people aware of the pangolin's plight and the problems with buying pangolin products. There are many ways you can support World Pangolin Day (buy a t-shirt, post something on social media, and much more). One fun way to celebrate is to create a pangolin suit for your dog! You can get the instructions here, along with lots of other ideas and information. So, the Pangolin deserves a place in the C.A.H.O.F. (Crackerjack Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word crackerjack was first used in America in the 1890s. Prior to that was the form, crackajack, which was a whimsical word for an excellent fellow (crack = an adjective meaning first-rate or excellent, jack = a noun meaning a buddy or fellow). Today, crackerjack basically means "a person or thing that shows marked ability or excellence." So, crackerjack is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Pangolin #1 - Geographical Pangolin with Lion - Daily Mail Pangolin Tongue - National Geographic Pangolin with Baby - Wildlife Reserves Singapore, via Zooborns Pangolin Dog Suit - Sarah Pappin via Pangolins.org

0 Comments

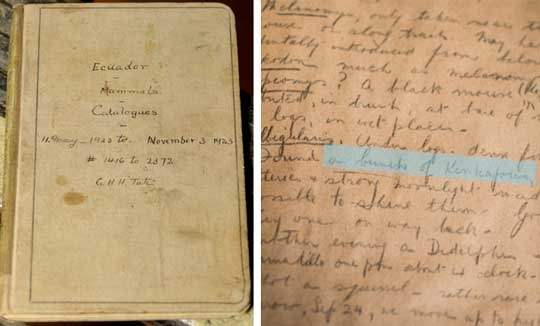

My last two Awesome Animals were insects, and creepy ones at that. And so it's time to feature a cute and cuddly animal. Well, at least cute—wild animals are rarely cuddly. I wanted to choose an animal that many of you may not be familiar with. I was able to come up with one that had only recently been discovered, the Olinguito! So, what the heck is an Olinguito? Pronounced oh-lin-GHEE-toe. This creature is a mammal in the family Procyonidae (racoons, coatis, ringtails, kinkajous, and a few others). They live in the mountainous forests of western Colombia and Ecuador (South America). Astoundingly, the olinguito was identified only a few years ago, in 2013, making it the first carnivore mammal species identified in the Western Hemisphere in 35 years! Amazing facts about the Olinguito First, I should point out that this creature wasn't exactly discovered in 2013. It had already been observed in the wild for over 100 years. But it was properly identified in 2013. This was the result of a ten-year study of a group of mammals called olingos. A Smithsonian scientist, Kristofer Helgen, studied olingos in an attempt to understand how many different species existed. By looking at a number of types of evidence, including shape of the teeth and DNA analysis, he and his team figured out that the olinguito is not an olingo at all. Instead, it is an entirely different type of mammal, living much higher in the mountains than any of the olingos (olinguitos live from 5,000 to 9,000 feet above sea level). The olinguito is known to the locals in Colombia and Ecuador as the "kitty bear." I'm guessing this is because these creatures look like a teddy bear but are the size of a kitten. If you need further proof that the olinguito is a cute critter, check out this immature: Olinguitos are what we call omnivorous frugivores. That's just a fancy way to say they eat mainly fruit (frugivore), but they also eat a variety of other stuff (omnivorous) such as insects and nectar from flowers. Olinguitos are the smallest members of the raccoon family, averaging only about two pounds (0.9 kg). There's an interesting story behind the discovery that the olinguito is a unique species. In 1923, scientists embarked on a six-month expedition in Ecuador to collect specimens of all types of animals to better understand the wildlife there. During the trip, 1,500 mammal specimens were collected. One of them, Mammal #66573, was incorrectly labeled as a kinkajou. Below is the original expedition journal and the page detailing the collection of the first olinguito (described as a kinkajou). This specimen sat in a drawer in the American Museum of Natural History for almost 90 years before being correctly identified. In the 1970s, there was a female olinguito (named Ringerl) that spent her entire life displayed in zoos around the United States. The creature had been mislabeled as an olingo. Ringerl was frequently moved from one zoo to another because she refused to breed with the other olingos (well, duh!). Ringerl was the first and only live olinguito in captivity at that time. In about 2003, a group of mammalogists led by Kristofer Helgen began a study of olingos by looking at museum specimens, and they came across the 1923 mislabeled specimen. By examining its skull, teeth, and fur, they decided it wasn't an olingo, it was a new species. So in 2006 they set out on an expedition to find out if this new species still existed in the wild. They found some of the animals and discovered they are nocturnal, they spend most of their time alone in the treetops, and they have only one baby at a time. With the help of DNA analysis, by 2013 Helgen's team was ready to declare the olinguito a new species. It took ten years to accomplish this! Check out this video of an olinguito The photo below is of Ringerl, the first olinguito in captivity, moved from zoo to zoo in the 1970s. Interestingly, the announcement of this new species resulted in kind of a "crowdsourcing" flood of information that has helped scientists understand the creature. Soon after the announcement, Dr. Helgen received thousands of emails from naturalists, birdwatchers, and other people with sightings and observations. For example, people at the Bellavista Reserve in Ecuador emailed him that they had figured out a way to track individual olinguitos and monitor their feeding and mating habits. At a reserve in Colombia, people provided the documentation of a baby olinguito and new details about how the animals breed and nest. As a result, we now know much more about this amazing creature. The olinguito story seems to appeal to everyone, including children. There have been several olinguito kids' books published in recent years. So, the Olinguito deserves a place in the B.A.H.O.F. (Bully Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word bully was first used in the 1530s. It was from the Dutch word boele, which means lover. The word became a popular adjective after the US president Teddy Roosevelt used it frequently to describe something's awesomeness. He used the term "bully pulpit" to describe his powerful pulpit from which to speak to the country. So, bully is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Olinguito #1 - Mark Gurney, Smithsonian Insider Baby Olinguito - Juan Rendon - Scientific American Ecuador Expedition Journal - D.Finnin - American Museum of Natural History Ringerl, the misidentified Olinguito - I. Popglayen-Neuwall - Smithsonian Institute One of the important themes in my newest novel Bridgers 4 is the ability of certain creatures to control the minds and behaviors of other creatures. In Bridgers 4, certain creatures can control even humans (you must read the book to get the bizarre and frightening details). I've selected an Awesome Animal that is notorious for this ability—the parasitic wasp. Actually, I should have featured these wasps closer to Halloween because they are kind of creepy. But, they're also absolutely fascinating. So, what the heck is a Parasitic Wasp? What I am referring to here is a family of wasps, called Ichneumonidae. Astoundingly, the ichneumonid (pronounced ick-noo-mon-id) wasps include over 60,000 species worldwide. Usually, when we think of wasps, we think of those nasty stingers. But the stingers of ichneumonid wasps have been modified to be ovipositors—a structure for laying eggs. And here is the fascinating (and creepy) part: they lay their eggs inside or on other creatures. Then their larvae, which are carnivorous, eat the host creature. And sometimes, the larvae actually control the behavior of the host, forcing it to do things that benefit the larvae. Below is an ichneumonid wasp laying its eggs in cabbage-eating caterpillars. Amazing facts about Parasitic Wasps First, I should point out that these wasps do not exactly fit the definition of parasite. Parasites (like ticks or tapeworms) rarely kill their hosts whereas these wasps almost always kill their hosts (the larvae consume the host creature). A more appropriate term is parasitoid. But I didn't want the title of this email to be too confusing, so I used the more familiar term. So, ichneumonid wasps are actually parasitoids. In Bridgers 4, Desmond, Lenny, and Xavier discuss an ichneumonid wasp that controls the behavior of orb-weaver spiders, so I'll begin with that amazing example. In the Central American tropics, there is a wasp that seeks out an orb-weaving spider, grabs the spider, and lays a single egg on the spider's abdomen. When the egg hatches, the worm-like larva attaches to the spider's abdomen and then starts sucking the spider's fluids out to say alive. See the larva attached to the orb-weaving spider below: For a while, this doesn't seem to affect the spider. But when the wasp larva gets to a certain size, it injects a chemical that changes the spider's behavior. The spider stops making its normal, symmetrical web it uses for catching insects. Instead, it makes a very specific type of web, one that is much stronger and that is perfect for safely holding the wasp larva's cocoon. When the spider finishes the new web, the larva kills and eats the spider. The wasp larva then creates its cocoon on this nice, custom-designed web. Check out this video about this wasp that forces spiders to weave a different web. The photo below on the left is the spider's normal web, and on the right is the web the wasp forces the spider to weave: The web on the right is stronger, requiring 2.7 to 40 times more force to snap the strands, compared to the normal web on the left. This makes the web more suitable for holding the wasp's cocoon. Also, the web on the right glows brightly when looked at under ultraviolet light, whereas the one on the left doesn't. This prevents insects and birds from accidentally flying into the web, again making it safer for the wasp's cocoon. Researchers believe the wasp larvae inject their spider hosts with chemicals that mimic hormones the spiders produce naturally to trigger them to build resting webs. And then slight modifications to the chemicals could force the spiders to go over the same spots to reinforce the web and to add the extra UV visibility. What an amazing example of mind-control! It's like something from a science fiction story, right? Oh wait... I actually use this concept in Bridgers 4. But wait, there's more! There are many, many examples of wasps that can change the behavior of their hosts, essentially turning them into zombie slaves. Another example is the emerald wasp and its much-larger victim, the common household cockroach. The wasp stings the cockroach in a very precise spot of the roach's brain, injecting mind-controlling venom. The cockroach suddenly loses its ability to initiate its own movement. The wasp grabs the cockroach's antenna and leads it to a special chamber. The cockroach follows along, unable to resist, making it much easier for the wasp to take the larger victim to its doom. Once it leads the cockroach to the chamber, the wasp lays a single egg on the roach and then seals up the chamber with pebbles. The wasp larva hatches out, burrows into the cockroach, and then eats the cockroach from the inside. I know... gross and creepy. But so cool! Hmm... I wonder where Ridley Scott got the idea for the alien larvae for his 1979 film, Alien. Below is the emerald wasp with its unfortunate victim: Okay, can you handle one more example without having nightmares? There is a wasp called the Ladybird Parasite. The adult females of this wasp seek out adult female ladybird beetles. The wasp lays a single egg on the beetle's belly. After about a week, the wasp larva hatches. It already has wicked mandibles, and it proceeds to remove any beetle larvae or eggs, and then it enters the beetle's body and starts feeding on the beetle's insides. The beetle goes about its business for almost a month while the wasp larva feeds within it. When the wasp larva is ready to emerge, it paralyzes the beetle first. It then tunnels out and forms a cocoon attached to the beetle's belly. The wasp in the cocoon develops beneath the ladybird beetle. Why? Well, ladybird beetles are brightly colored to scare away potential predators (the beetles secrete a nasty tasting chemical). And so the paralyzed beetle becomes the developing wasp's zombie bodyguard. The beetle even twitches its legs regularly, which helps to scare predators away. The photo below shows these zombie bodyguards with wasp cocoons beneath them. I wish I could go on and on about animals that control the minds of other animals. There are even examples of parasitic fungi that do this! But, those will have to be topics for future Awesome Animal emails. Well... maybe in the next email I should feature an animal that is cute and cuddly? So, the Parasitic Wasp deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Formidable Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word formidable has been around since the early 1400s. It has several meanings, such as causing apprehension or dread, of awesome strength, and arousing feelings of awe because of grandeur or strength. Due to creepiness and horrifying habits of parasitic wasps, I thought this word was a good choice today. So, formidable is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Wasp laying eggs in cabbage-eating caterpillar - Phys.org Wasp larva on orb-weaving soider - NY Times Orb-weaver web comparison - Smithsonian Insider Emerald Wasp and cockroach - Deven Dadhawala on Flickr Lady beetles carrying wasp cocoons - BBC |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed