|

There are two reasons why I chose the reindeer for this post. The first one is obvious, right? It's close to Christmas. The second reason? Because reindeer play a role in the upcoming first book in my new series. The series is titled Across Horizons, and it is my own twist on time travel (more information on the series in future newsletters). The first book takes place 47,000 years in the past, when reindeer roamed much of the northern hemisphere in vast herds. At the time, there were also cave lions, cave bears, woolly rhinos, and countless other impressive mammals... but again, more on that later. What the heck is a Reindeer? Everyone has heard of reindeer, but does everyone know much about the actual wild animal? First, you should know that in North America these creatures are called caribou. Yep, caribou and reindeer are the same species. As the name suggests, they are a species of deer, with the scientific name of Rangifer tarandus. They are all the same species, but there are at least 13 different subspecies, usually separated into geographically distinct "herds." Amazing facts about Reindeer Reindeer have what's called a circumpolar distribution. This means they exist all the way around the world at far north latitudes (near the North Pole). So, they can be found in the cold, northern regions of North America, Greenland, Europe, and Siberia. Reindeer have impressive antlers. In fact, relative to body size, they have the largest, heaviest antlers of all the living species of deer. A male's antlers can reach up to 51 inches (130 cm) long. Moose can have larger antlers, but they also have much larger bodies. Keep in mind that antlers and horns are not the same thing. Antlers are made of bone, they usually are branched, and they grow and fall off every year. Antlers are features of the deer family (Cervidae). Horns have a bony core covered by a keratin sheath (keratin is the protein that makes up hair, skin, and fingernails). Horns, which are a permanent part of the body and do not fall off, are features of the Bovidae family (cattle, sheep, goats, bison, and others). Reindeer are the only species of deer in which both males and females grow antlers. Here is an interesting thought. Male reindeer start growing their antlers in March or April and then shed them by early December (before Christmas). Female reindeer start growing their antlers in May or June, and they don't shed them until they start having calves in the spring. Hmm... In every movie or picture of Santa and his sleigh, the reindeer have antlers. This means all those reindeer are FEMALE. Oh no, my head is going to explode! I've always thought Rudolph, and at least some of the others, were boys. Well, hold on a second... The timing of antler shedding in males can sometimes be affected by other factors. For example, young males can keep their antlers longer. Also, males that are neutered may not lose their antlers until April. Do we dare imagine that Santa may have neutered his reindeer? Anyway, reindeer antlers can be quite impressive. Although reindeer all belong to one species, the various subspecies can be quite different. In some subspecies, the males can grow to over 550 pounds (250 kg). The males of the smallest subspecies, the Svalbard reindeer, average only about 150 pounds (68 kg). Hmmm... let's think about this. The very first time people were introduced to the idea of Santa having reindeer was in 1823. This was when Clement C. Moore published his poem, "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" (also known as "Twas the Night Before Christmas" from the poem's first line). In this poem, Moore described the reindeer as "tiny." That makes sense to me—we certainly don't need a 550-pound reindeer falling through the roof. So... logically, Santa's reindeer must be Svalbard reindeer. But this means that all the movies have it wrong, as they always use huge, full-sized reindeer. So confusing! As I said, the first mention of Santa having reindeer was Moore's poem. Moore provided the names Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem. Wait, what? Dunder and Blixem? Eventually, these last two were changed from Dutch to German, and they became Donner and Blitzen. But still, these two stand out. Why? Because all the others make sense in English. In German, Donner means "thunder" and Blitzen means "flash." While I'm on a roll with Santa connections, what about Rudolph? Well, he (or she...?) wasn't introduced until 1939. That's when Robert L. May, a catalog writer for Montgomery Ward, wrote a children's book for the department store. The book was written in verse, and May titled it, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” Here's what the original looked like: Hmm... no antlers on the original Rudolph. In fact, it didn't look much like a reindeer at all. Okay, I have to address something I've wondered about all my life. Where did the idea come from that reindeer could fly? For my benefit and yours, I did a bit of research on this. As it turns out, this idea might be much older than you think. The anthropologist Piers Vitebsky, in his book "The Reindeer People," provides details of Reindeer Stones. These are stones that ancient people (as long ago as 3,000 years) embedded vertically in the ground. Reindeer stones are found in various places throughout the world but particularly in Siberia and Mongolia. Various animals were carved upon these stones. However, one animal was carved far more often than any other—the reindeer. The odd thing about these carved reindeer is that they are depicted with their neck outstretched, their front legs flung out in front, and their back legs flung out behind. And often the sun is framed within the creature's antlers, as if the artists were depicting the reindeer flying through the sky. Below is a set of "reindeer stones." So, perhaps some ancient peoples thought of reindeer as having superpowers, including the ability to fly. The Pazyryk people were an ancient nomadic culture in the Altai mountains of Siberia. Their mummified remains are really cool because these people had a habit of covering their bodies with elaborate tattoos, and many of these tattoos are still clearly visible. Guess what was often depicted in their tattoos.... yep, flying reindeer. Below is an actual mummified tattoo depicting a reindeer that seems to be flying. The image is shown more clearly on the right. Notice that this tattoo even shows the reindeer with a bird's beak. So, it seems that the idea of flying reindeer is not a new concept at all. Now, back to real reindeer... Some reindeer subspecies migrate, others don't. Those that do migrate, though, can be pretty impressive. A few populations of reindeer in North America migrate farther than any other land animal, up to 3,100 miles each year. To accomplish this, they average about 23 miles per day. Sometimes these migrating herds can include as many as 500,000 individuals! Check out this video of the Western Caribou Arctic Herd in Alaska. Rivers and lakes don't slow the reindeer down as they migrate. Adults can swim long distances at 4 mph (6.4 km/hr), and they can swim 6 mph (10 km/hr) when they are in a real hurry. Check out this video of a swimming herd. A migrating herd of thousands of reindeer must be an amazing sight to see. One last random fact: An entire reindeer was once found inside the stomach of a Greenland shark. I just thought you might want to know that. So, the Reindeer deserves a place in the P.A.H.O.F. (Primo Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word primo originated in the mid 1700s. In Italian it literally means first. By the late 1700s it was primarily a musical term, meaning the first or leading part in an ensemble. Much more recently, the word has been adopted to describe something as excellent or first class ("That's a primo flying reindeer tattoo you got there."). In the1990s, it was often used as street slang to describe the high quality of drugs ("This is some primo weed, man!"). So, primo is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Reindeer herd #1 - Creative Commons via pxfuel.com Reindeer with big antlers - National Park Service Rudolph book - Rauner Special Collections Library/Dartmouth College via NPR Reindeer stones - Alix Guillard, Wikimedia Commons, via Earthtouchnews Reindeer tattoo - SiberianTimes via DailyMail Large reindeer herd - ADF&G via National Park Service

2 Comments

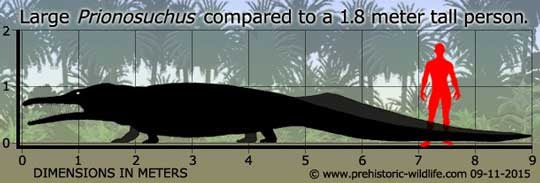

I can't help it. I have to feature another amphibian (in my last post I featured the Caecilian). After all, Bridgers 6 is filled with awesome amphibians, so these critters are on my mind lately. Bridgers 6 takes place on an alternate version of Earth teeming with creatures descended from amphibians. There are big ones, small ones, scary ones, and tall ones! What's the biggest amphibian on our own version of Earth, you ask? Without a doubt, it's the Chinese giant salamander. What the heck is a Chinese giant salamander? Hiding in rocky streams in the Yangtze river basin of central China is an amazing salamander that grows to six feet (1.8 meters) long and weighs up to 110 pounds (50 kg). They are known to live at least sixty years, and possibly much longer. For a long time, scientists thought there was only one species, but genetic analysis indicates there are probably three or more distinct species. Giant salamanders belong to the family Cryptobranchidae. There is actually one other member of this family, the hellbender (also known as the snot otter), which grows to two feet long and lives in the eastern United States (I featured the hellbender back in May). Amazing facts about Chinese giant salamanders Giant salamanders are considered living fossils because the Cryptobranchidae family has been around for 170 million years. Much of their history was during the time of dinosaurs! They have changed very little during all that time. Giant salamanders spend their entire lives under water. Surprisingly, though, they do not have gills. Heck, they don't even have lungs. They get their oxygen by absorbing it directly through their skin. So, as you would expect, they need to live in streams with fast-moving, highly-oxygenated water. See all those folds of skin on the creature's sides? Those folds increase the surface area of the skin, which in turn increases the amount of oxygen absorbed. Giant salamanders are predators, and they eat almost anything that moves and will fit in their mouth. They will suck up aquatic insects, worms, frogs, other salamanders, freshwater crabs, shrimp, and fish. They even eat smaller individuals of their own species, In fact, one study found that 28% of all the food found in the bellies of 79 giant salamanders was other giant salamanders. Above I mentioned that they suck up their prey. This is called the gape-and-suck method, and it's actually a highly effective way to feed (many fish do this too). Here's how it works. When they sense prey in front of them, they greatly increase the size of their throat and pop open their mouth. This creates a powerful sucking action and draws in water, as well as any unfortunate creature swimming in the water. To make this even more effective, they displace their jaw in the process. This entire motion takes place in just a fraction of a second. Check out this slow-motion video of how powerful this prey-sucking methods works! I also mentioned above that giant salamanders "sense" the prey in front of them. They have very poor eyesight. Instead of seeing their prey, they have rows of special sensory nodes along each side of their body, from their head all the way to their tail. These sensory nodes allow them to detect the tiniest of vibrations in the water. So they "see" by detecting the vibrations other creatures create. This must work pretty well, because they catch enough prey to grow to over a hundred pounds! Sure, the Chinese giant salamander is a big amphibian, but is it the biggest amphibian ever? Not even close. About 275 million years ago, in the swamps and rivers of an area that is now Brazil, lived the Prionosuchus. Amazingly, Prionosuchus grew at least 30 feet long and weighed 4,400 pounds (2,000 kg). Prionosuchus was the amphibian version of a crocodile (does this sound familiar to those of you who have read Bridgers 6?), or more accurately, a gharial, a fish-eating crocodile with a long, narrow, toothy snout. The diagram below gives you an ideas of the size of the Prionosuchus. Keep in mind this creature was an amphibian! There is an interesting story behind the first identification of giant salamanders. Surprisingly, scientists knew about giant salamanders from fossils before discovering living specimens. In 1726, Johann Scheuchze described a fossil giant salamander from Switzerland. He mistakingly believed the fossil was of a human that had drowned in the biblical flood, the Deluge. So he gave the fossil the name Homo diluvii testis. In Latin, this means Man, a witness of the Deluge. The fossil (shown below) was about three feet (1 m) long, and the tail and hind legs were missing, so Scheuchze assumed it was a human child that had been violently trampled, perhaps in an attempt to escape the Deluge. In 1758, another scientist decided the fossil was a catfish. Then in 1787, another scientist decided it was a lizard. In 1809, yet another scientist concluded that it was "nothing but a salamander, or rather a proteus of gigantic dimensions and of an unknown species." Hmm... biology has come a long way in the last 250 years, hasn't it? Interestingly, in 1837, when the giant salamander was given its genus name (the name still used today), it was named Andrias. This means image of man. And scheuchzeri was assigned as the species name. These two names together honor Johann Scheuchze and his (mistaken) beliefs. By the way (I can't help mentioning this), the species Andrias scheuchzeri was used by the Czech author Karel Čapek in his 1931 science fiction novel, War with the Newts (also translated as War with the Salamanders). In the Pacific, a race of intelligent salamanders are found. They are enslaved and abused. But then they rebel, which leads to a global war for species domination. This satirical book is considered by many to be the first ever dystopian sci-fi novel, and many consider it to be the best science fiction book ever written. Chinese giant salamanders have inspired numerous myths and legends in Chinese culture. In fact, the commonly-seen yin and yang symbol is thought to have originally been two giant salamanders intertwined harmoniously. Also, these salamanders are often called wa wa yu, which means baby fish. Why? Because the giant salamander's distress call sounds like a human baby crying. Check out this brief video about the Chinese giant salamander. Okay, one more thing about the Chinese giant salamander. These creatures were once common in the rivers across southeast China. Unfortunately, now they are critically endangered in the wild. They have become a fashionable delicacy among the wealthy, and this has resulted in almost complete decimation in the wild from poaching. Today most giant salamanders are found on commercial farms that raise them for food, sometimes bringing $1,500 per salamander. The Chinese government encourages the farms to release some of their salamanders into the wild. At first, this seems like a good idea. BUT... scientists have found that the farm-raised salamanders are genetically different from those in the wild. It seems the wild salamanders can easily be divided into five very different genetic groups, and the groups split apart from each other millions of years ago. But the farm salamanders are a result of extensive genetic mixing. So, the original genetically-distinct types in the wild are quickly being replaced by these new, artificially-mixed salamanders that never existed before. Hmm... an interesting dilemma. So, the Chinese Giant Salamander deserves a place in the B.A.H.O.F. (Boffo Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word boffo was first recorded in use in the 1940s. Basically it means sensational or extremely successful. By the 1960s, the word was commonly used in show business. This usage is thought to have originated in the Hollywood trade magazine Variety. Example: "It was a boffo performance, impressing even the harshest critics." So, basically, boffo means it's a hit. In spite of the giant salamander's recent troubles (being endangered), the fact that the creature has been around for 170 million years indicates a boffo performance (evolutionarily speaking). So, boffo is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Indian pipe - Stan C. Smith Man holding giant salamander - Pinterest Giant salamander in river - San Diego Zoo Girl with salamander in zoo - Getty Images via DailyMail Giant salamander fossil - Wikimedia Recently, I spotted this frog clinging to the corner of one of our little bird houses. In spite of its mostly green color, this is a gray treefrog. These frogs can change their color, and they are actually gray more often than they are green. But when they are surrounded by green vegetation, their skin turns green like the one in this photo. You know, like a chameleon. Let's think about this for a moment... their skin changes color to better conceal them. Wow. Perhaps amphibians are under-appreciated for their awesomeness. Consider the Olm, a blind salamander with transparent skin that lives underground, hunts for its prey by smell and electrosensitivity, and can survive without food for 10 years (seriously). Then there's the Chinese giant salamander that can grow up to 1.8 meters in length and evolved independently from all other amphibians over one hundred million years before Tyrannosaurus rex. And there's the Chile Darwin’s frog—the fathers protect the young in their mouths. And the Gardiner’s Seychelles frog, the world’s smallest frog, with adults growing up to be the size of a pencil eraser. And let's not forget about the caecilian, a legless amphibian that... oh, wait... the caecilian is today's Awesome Animal. Let's take a more careful look. Have you ever heard of a glass lizard? It looks like a snake, but it's actually a lizard without legs. Well, the caecilian is kind of the glass lizard of the amphibian world—an amphibian with no legs. Actually, at first glance a caecilian looks like an earthworm. Check it out: What the heck is a Caecilian? First, Caecilian is pronounced seh-SILL-yun (almost like the pizza). Second, caecilians are amphibians, but they aren't frogs, they aren't toads, and they aren't salamanders. So what are they? They're caecilians, of course! Caecilians are their own order within the class Amphibia. In case you care, the order is called Gymnophiona (some scientists prefer to call the order Apoda, which means 'without feet'). Caecilians live on just about every continent that has moist tropical regions, including Southeast Asia, India, East and West Africa, Indonesia, and Central and South America. Caecilians are the least known of the amphibians. One reason for this is that most of them spend their time underground (that's why they look like earthworms). Some of them are so secretive that it's almost certain that there are species we have not yet discovered. We now know of about 200 species. In fact, to celebrate the discovery of the 200th species, the musical group called the Wiggly Tendrils (this is a real band!) recorded a song titled Caecilian Cotillion. Check out the Caecilian song! Amazing facts about Caecilians Where to even begin! Get ready to be amazed, because Caecilians are bizarre creatures. Not all caecilians look like gray earthworms. They are kind of like gummy worms—they come in all colors and sizes. Check out this blue species: And not all of them live in the soil. Some of them are perfectly at home in the water. Check out this aquatic caecilian: The smallest species of caecilians are only a few inches long, but the largest (Caecilia thompsoni from Colombia) can grow to five feet (1.5 m) long and weigh 2.2 pounds (1 kg). Five feet long!? What would a five-foot caecilian look like? You would think it would be fat and heavy-looking, but not so much: When it comes to reproduction, frogs and toads have what's called external fertilization. That means the female lays eggs, and then the male fertilizes the eggs outside of the female's body. But caecilians have internal insemination. The males have a long, tube-like organ called a phallodeum, which is inserted into the female's cloaca for about three hours (I guess they aren't in any hurry). As you can probably guess, sperm cells are transmitted into the female's body through the phallodeum, where they fertilize the eggs. Some caecilians lay eggs, some have live birth, but I feel compelled to nominate female caecilians for Mother of the Year. I'll explain why. In some caecilian species, the mother seals herself in a subterranean cavity, where she lays her eggs. The eggs hatch, and the mother and babies remain in the cavity for four to six weeks as the babies grow. What do the babies eat, you ask? Here's where it gets weird. After the female lays eggs, her skin begins to thicken, and the skin cells fill up with fats and other nutrients. The newly-hatched babies have special teeth that are like scrapers, and they literally eat the skin off the mother. The mother grows more skin, and the babies eat that skin, too. This continues until the babies are ready to leave home and go out on their own. So the mothers literally feed the babies their own skin, over and over. Even more bizarre, in some of the species that have live birth, the babies inside the mother's body use their special teeth to munch on their mom's reproductive organs! Like I said, Mother of the Year. Caecilians have teeny tiny little eyes that don't see much, or don't see at all. These eyes are usually subcutaneous (buried under the skin), and some species even have bone over their eyes! There's not much need for eyes when most of your life is spent in the dark. Not much is known about what Caecilians eat in the wild, but in captivity they readily chomp on earthworms, so worms are probably a normal part of their diet. In a study of the gut contents of 14 dead caecilians, the only identifiable objects were termite heads. That doesn't mean caecilians go around biting off the heads of termites, it just means that the heads are the portion that is most difficult to digest. Although caecilians look like they are all tail, they actually don't even have tails. Their cloaca (that's the polite word for their butthole) is at the very end of their body. Most caecilians breathe with lungs, but scientists were amazed to find some species without any lungs at all. Wow... eyes, legs, tails, and now lungs—caecilians seem to be all about giving things up. Apparently these lungless species can get all the oxygen they need by absorbing it directly through their skin. Here's a lungless caecilian found in Brazil: Caecilians have super-strength. They need to be strong to push their way through the soil. Scientists at the University of Chicago wanted to find out how hard caecilians could push against soil. They set up an artificial tunnel and filled one end with dirt and put a brick at that end to stop the caecilians from burrowing any farther. To measure how hard the caecilian could push, they attached a device called a force plate. The results were a surprise. They used a caecilian only 1.5 feet (50 cm) long. “It just shoved this brick off the table,” one of the scientists recalled. Because of this amazing soil-pushing strength, caecilians have developed extra-thick, reinforced skulls to prevent serious head damage. So, the Caecilian deserves a place in the F.S.A.H.O.F. (Four-Star Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The phrase four-star was first recorded in use in the early 1920s. Basically it means of a superior degree of excellence. The phrase started as the number of asterisks used to denote relative excellence in guidebooks (for example, a four-star restaurant, or a four-star hotel). It also indicates being a full general or admiral, as indicated by four stars on an insignia. As with many other such words, four-star eventually was used to describe just about anything of high quality (the caecilian is a four-star amphibian). So, four-star is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Caecilian #1 - Michael & Patricia Fogden/CORBIS via WIRED Blue Caecilian - Unknown, via beetleboybioblog Aquatic caecilian - National Zoo Longest caecilian - Reptilis.org Blue and black caecilian with babies - Alex Kupfer via Science News for Students Lungless caecilian - B.S.F. Silva via Science News for Students |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed