|

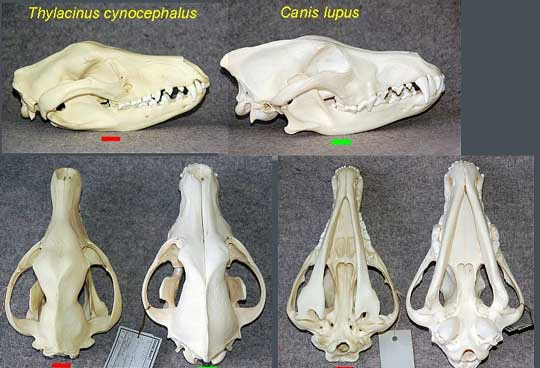

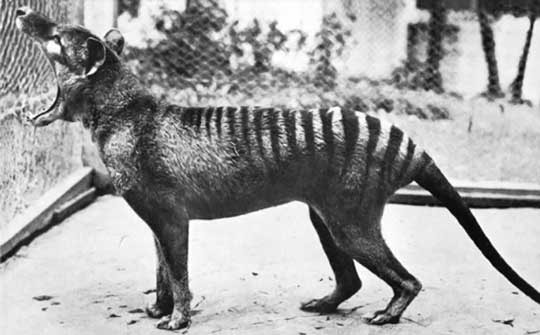

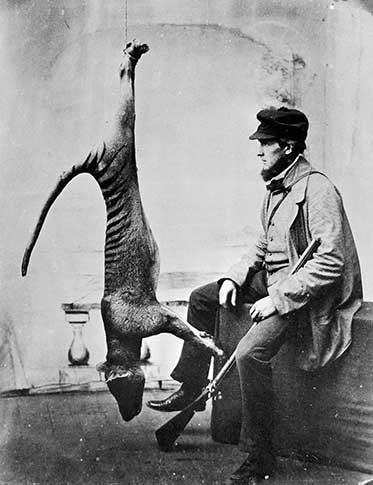

You know, there are some animals that humans really wish still existed. One example is the ivory-billed woodpecker in North America. The last universally-accepted sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker was in Louisiana in 1944. But diehard birders never stop searching, hoping to be the first to discover that this species still exists. And there are numerous unconfirmed sightings. So I guess the ivory-billed woodpecker is kind of like Elvis. In Australia, and particularly in the Australian island state of Tasmania, people are still looking for the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the Thylocine. Yep, they're still looking, even though the last of these creatures died in 1936. The Tasmanian tiger is, no doubt, an awesome animal, so let's take a closer look. We'll also take a closer look at the never-ending search for this creature. What the heck is a Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine)? First, the thylacine is a marsupial. You know what marsupials are, right? They are a group of mammals that give birth to very small young, which are then nurtured in an external pouch (includes kangaroos, koalas, opossums, wombats, and many more). Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, nurture the fetus inside the body, with a placenta that helps exchange nutrients and waste between the mother's blood and the fetus. The thylacine is one of the largest known carnivorous marsupial (marsupials that prey on other animals). At one time, the thylacine was fairly common in Tasmania, New Guinea, and throughout the Australian mainland. The thylacine was what we call an apex predator, which means it was at the top of the food chain in its range (it had no natural predators). Although the thylacine is not related to dogs, it has a general dog shape. Because of this, it is sometimes called the Tasmanian wolf. The name Tasmanian tiger comes from the row of stripes on its back. Amazing facts about the Thylacine The thylacine is one of only two marsupials in which both males and females have a pouch. You already know what the female's pouch is for. The male's pouch serves as a protective covering for the external reproductive organs. Wait, what? That sounds like a no-brainer. Why don't all male mammals have those? Anyway, the only other marsupial that has this protective pouch in males is the water opossum. The thylacine is a great example of what we call convergent evolution, in which unrelated creatures end up having similar structures because they have become well adapted to similar niches. The thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog has filled in other areas of the world. That's why it looks similar to a dog! The skull below on the left is from a thylacine, and the skull on the right is from a timber wolf. Notice how similar they look, even though they are not closely related at all. Since these creatures went extinct in the 1930s, we don't know much about their behavior. But from early recorded observations, we know that they ran with an odd, stiff gait, which made it difficult for the animal to run very fast. Occasionally they were also observed hopping on their back legs like a kangaroo. It is thought that they used this hopping motion when startled. The thylacine also had an amazing ability to open its mouth, spreading its jaws to 80 degrees! Here's a 1933 photo of a thylacine yawning (which is a threat gesture). What a mouth! How did the thylacine go extinct? As stated above, thylacines once lived throughout mainland Australia and in parts of New Guinea. They went extinct in these places about 2,000 years ago. Although there is disagreement as to how the creature went extinct on the mainland, it is thought to be at least partly due to the arrival of the dingo (a dog native to Australia). But more recent studies suggest it may have been caused more by climate change and by the way Aborigines used the land. The dingo theory is debatable because the two animals are thought to have different hunting habits and prey. Why does this matter? Because if they had different prey, they probably did not compete with each other as much as we once thought. However, the thylacines that had been isolated on the island of Tasmania escaped this fate (maybe because there are no dingoes on Tasmania). Even so, only about 5000 thylacines still lived in Tasmania when the first Europeans settled on the island in 1803. This is when things really went downhill for the Tasmanian tiger. Soon after Europeans settled on Tasmania, they started complaining that thylacines were killing their sheep. Actually, there was more evidence that feral dogs and poor farming habits were really the culprits, but the farmers must have decided that the thylacine was easier to blame. By the 1830s, the farmers pooled their money and established a system of bounties for killing thylacines. And then the government started awarding bounties. By the time this practice ended in 1909, a total of 2,180 bounties had been awarded. Below is a photo of a hunter posing with his "trophy" in 1869. This excessive hunting, combined with habitat destruction, the introduction of foreign diseases, and competition from feral dogs decimated the population, and the last thylacine in the wild was shot in 1930. At that time there was a shift in public opinion about thylacines, and preservation measures were put in place. But—you guessed it—this was far too late. Just 59 days after the species was granted "protected" status, the last individual in captivity died at the Hobart Zoo. Its name was Benjamin, and it died because the zookeepers accidentally locked Benjamin out of his sheltered sleeping quarters on a very cold night (I should point out, though, that these details about the name and the accident are now being challenged and may not be accurate). Here is a photo of Benjamin, taken in 1936, not long before he died: People are still searching for Tasmanian tigers Ever since the thylacine's extinction, many Australians have searched for these animals. In fact, some have devoted their entire lives to the search. But no definitive evidence has ever been found. No definite photos, no definite videos, no definite sightings by highly-qualified scientists. You might be tempted to equate this with the search for Bigfoot in North America, or the search for "Nessie" in Loch Ness in Scotland. But... remember that the thylacine is a REAL animal, and it definitely lived only 83 years ago. Is it likely to be alive? Probably not. Is it possible? Absolutely. And what's interesting is that people have consistently reported sightings over the last 80 years. In Tasmania, hundreds of unconfirmed sightings have been reported. Astoundingly, 65 sighting have been reported on the Australian mainland, particularly in the southwest portion of Western Australia. And more recently sightings have been reported in northern Queensland. But... not one single confirmed photo, video, or sighting. Hmm... What do you think? With all the technology we now have, especially trail cameras, wouldn't we have at least ONE definitive video or photo? Perhaps the most intriguing video was captured by teacher Paul Day. Paul was photographing the sunrise in the Yorke Peninsula in northern Queensland when a creature ran across a field in front of him. The creature's strange hopping gait is much like what observers have described for the thylacine. Check out the video! I know, we all want to believe the Tasmanian tiger still exists. How cool would that be? But, perhaps we should remain skeptical, at least until someone comes up with undeniable proof. Again, what do you think? So, the Tasmanian Tiger deserves a place in the. B.O.A.A.H.O.F. (Bit of Alright Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The phrase bit of alright, as far as I can tell, is mainly used in Australia (making it especially suitable for the thylacine) and Great Britain. Typically it is used to describe someone as physically attractive (Example: "He's a bit of all right, isn't he?" said Isadora, looking at a tall man near the door.). Well, the Tasmanian tiger, in my opinion, is a very attractive creature (as extinct marsupials go), so bit of alright is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Tasmanian tiger #1 - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via National Museum Australia Thylacine and wolf skulls - Wikipedia Tasmanian tiger yawning - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via University of Melbourne Tasmanian Tiger (Benjamin) - Getty Images via Foxnews.com Screen shot of Paul Day's Video - National Geographic

0 Comments

Way back in 1995, Trish and I had a special opportunity to visit New Zealand with a group of about thirty other science teachers. One of the places we visited was the Aukland Zoo. What a spectacular place! I was thrilled to see so many animals that I had never seen before other than in photographs. But what I most anticipated seeing was the tuatara. At first glance the tuatara looks like a lizard, like a rather bland version of some kind of iguana. But I knew that this creature was much, much more than that. The tuatara is, in fact, one of the most unusual reptiles alive today. Read on to learn more... What the heck is a Tuatara? Tuataras look like lizards, but they aren't lizards. Lizards and snakes belong in an order called Squamata. The tuatara is in a completely different order all by itself, called Rhynchocephalia. That's a mouthful: rink-oh-ceph-ale-ya. Only one species of Rhynchocephalia (the tuatara) survives today, and it only lives in New Zealand. But there was a time, millions of years ago when dinosaurs roamed the earth, when there were many species, even some bizarre marine species. The Rhynchocephalia were once probably as abundant as lizards are today. Why is the tuatara NOT a lizard? Hmm... where to begin... Amazing facts about the Tuatara Back in 1831, a British zoologist by the name of John Edward Gray discovered the tuatara (yes, I know—he didn't really discover the species... the native Maori were aware of it long before then). He sent a skeleton to the British Museum, and it was misidentified as a lizard. It wasn't until 1867 that another scientist named Albert Günther examined the skeleton and realized that it actually had features seen in crocodiles, turtles, and birds! So Günther proposed creating the order Rhynchocephalia just for this creature. So we've known for 152 years that the tuatara is not a lizard! If the tuatara isn't a lizard, is it a dinosaur? Nope, not a dinosaur either, although they were abundant while dinosaurs were around. First, to fully appreciate how unique the tuatara is, let's consider this: The huge group of animals called “amniote vertebrates” includes mammals (6,495 species), turtles (341 species), birds (15,845 species), crocodylians (25 species), lizards and snakes (10,078 species). And then there's the Rhynchocephalia... with ONE species, the tuatara! Let's look at what makes tuataras so unique. First, they have a third eye. What? A third eye? Well, kind of. This third eye is situated just where you would expect it to be—on top of the forehead. It's actually known as a parietal eye. It really does have a lens and a retina, but it is more primitive than the tuatara's regular eyes, and can mostly just detect the presence or absence of light. The exact purpose of the eye is not fully understood, but it is thought to help the tuatara judge the time of day and the season, which would help it with thermoregulation (maintaining its body temperature). I should point out that tuataras are not the only animals to have parietal eyes. They are found in some burrowing lizards, some frogs, and some fish, including sharks. But the parietal eyes of the tuatara are more developed than these others. The photo below points out where the parietal eye is on a tuatara. One of the most distinctive features of tuataras (that sets them apart from other reptiles) is that they have a second row of upper teeth. When they close their mouths, the one row of teeth on the lower jaw fits nicely between the two rows on the upper jaw. Actually, they are not even real teeth at all. Unlike other reptiles, their teeth are not separate structures. Instead, they are simply sharp projections of the jaw bone. Therefore, the "teeth" are not replaced when they break off. Because of this, the "teeth" gradually get worn down as the tuatara grows older. So, old tuataras have to switch to eating only soft prey like earthworms and grubs. Eventually they have to chew their food with nothing more than smooth jaw bones. Too bad old tuataras can't get dentures, huh? Check out the tuatara skull below. You can see the rows of "teeth" on the sides. You can also see the beak-like front teeth (lizards don't have those), as well as the strange arches behind the eyes (lizards don't have those either). There are other aspects of this skull that separates tuataras from lizards, but I have to be honest—they are beyond my ability to accurately describe them! Speaking of those "teeth," tuataras do not chew like lizards chew. Instead of chewing up and down, the jaws of tuataras have a forward-and-backward sawing motion, slicing food like a steak knife. This apparently works well—tuataras can chew through chiton and bone. It allows them to eat tougher prey. In fact, they are known to decapitate birds (headless bird bodies are often found near tuatara nests). Tuataras are extremely tolerant of cold (for a reptile). I seem to remember a Gary Larson cartoon with a crocodile on the witness stand angrily telling the prosecutor, “Well, of course I did it in cold blood, you idiot! I’m a reptile!” But in reality, most reptiles become very lethargic in colder temperatures (making it so that the crocodile would be incapable of committing the crime in question). But not so the tuatara. They have a unique type of hemoglobin in their blood that allow them to be active at temperatures only a few degrees above freezing. Not only that, but they can hold their breath for up to an hour! This slow metabolism makes it so that tuataras have really slow development and really long lifespans. I mean really long. It takes a tuatara a whopping 14 years to reach sexual maturity, and it takes 35 year for them to be fully grown. Once mature, it takes the females up to three years to produce eggs with yolk. And THEN it takes twelve to fifteen months from copulation to hatching! During that time, it takes up to seven months just to form the egg shells. Yeesh. Not in much of a hurry, are they? Check out this video about hatchling tuataras. So, if it takes 35 years to grow up, how long can these things live? Astoundingly, the oldest tuatara that we know of is Henry. Henry the tuatara lives in the Southland Museum in Invercargill, New Zealand. Henry became a celebrity when he finally decided to mate with a female at the age of 111 (like I said, not in a hurry). That was in 2009, so now Henry is 121 years old. Henry had the honor of meeting Prince Harry at the age of 118 (that was the age of Henry, not Prince Harry). So, the tuatara deserves a place in the. F.A.H.O.F. (Fabuloso Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word fabuloso comes from the Latin fābulōsus (which means fabulous, great, wonderful). It is somewhat difficult to trace the origins of its use in the English language because it is also used in several other languages (including Portuguese and Spanish). But from what I can tell, it is used to add a particular stylistic flair to the word fabulous (making it more flamboyant and expressive). Oddly enough, it is also the name of a multi-purpose cleaner used for cleaning bathrooms, tile floors, and such. Anyway, fabuloso is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

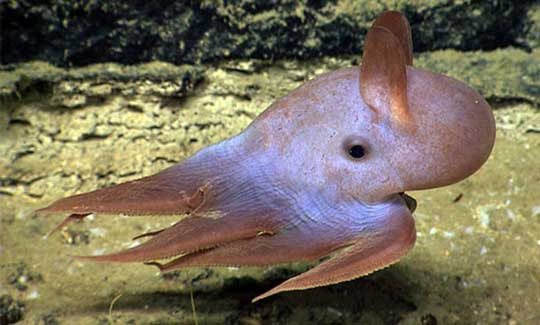

Tuatara #1 - San Diego Zoo Tuatara #2 - somaholiday/Flickr via AustralianGeographic.com Parietal eye - c00lbeans69 via Imgur Tuatara skull - Museum of New Zealand Henry with Prince Harry - Tim Rooke/REX Shutterstock via The Telegraph Did you know the most common (and accepted) plural word for octopus is octopuses? It is not octopi. Actually the proper word is octopodes. Here's why: If the word octopus had come from Latin (like syllabus or alumnus), the correct plural form would be octopi. But octopus actually came from Greek, and in Greek the correct plural is octopodes. But the word octopodes never really caught in, so most people use octopuses. And... did you know octopuses are mollusks? Yep, they are in the same animal phylum as snails, slugs, clams, oysters, and squid (as well as many others). I know... they don't look anything like a snail or a clam, right? AND... did you know there are about 300 species of octopuses? And if there is one type that deserves to have squishy toys made in its image—it has to be the dumbo octopus. What the heck is a Dumbo Octopus? Dumbo octopuses include about 13 species of umbrella octopuses (a group that kind of look like an umbrella when they spread their tentacles). The name dumbo comes from the fact that they have two fins that spread out above the eyes, resembling the oversized ears of Dumbo the elephant (from the 1941 animated Disney film). Actually, very little is known about the dumbo octopus, but we know enough to be confident that they are awesome! Let's take a look. Amazing facts about the Dumbo Octopus You're not going to see a dumbo octopus while you're out snorkeling in shallow water. Why? Because these octopuses live deep in the ocean. Most of them live at depths of about 13,000 feet (4,000 m), and some have been found as deep as 23,000 feet (7,000 m). That's over four miles down! Chances are, they live even deeper than that. This makes them by far the deepest living of all the octopuses. Dumbo octopuses appear to move through the water by slowly flapping their ear-like fins, but actually they are gently squirting water from their tentacle-funnel, and their ear fins are providing stability and steering. They can also crawl along the sea floor with their tentacles (you can call them arms if you want, but I just like to say the word tentacles). Since these methods of movement are slow, to escape from predators they also can dart away by aggressively squeezing water out. They do this by expanding and contracting their tentacles, making use of the funnel-like webbing between their tentacles. Dumbo octopuses are fairly small, averaging about 8 to 12 inches (20-30 cm) long, about the size of a guinea pig. But larger ones have been found. The largest of these was 5 feet 10 inches (1.8 m) long and weighed 13 pounds (5.9 kg). I guess you could call that one a jumbo dumbo octopus. Since dumbo octopuses live so deep, they are not threatened much by human activity. But they do have to worry about sharks and predatory cephalopods (such as larger octopuses and squid). Dumbo octopuses are quite rare and difficult to find, so we don't know much about their population size, and we really don't know if they are threatened or if they simply are naturally scarce. Dumbo octopuses may look cute and cuddly, but they are efficient and deadly predators. They typically float around in the open water, gently flapping their "dumbo ears" (fins), and when they find a fish or other prey, they pounce on it quickly and swallow it in one gulp. Their most common prey animals include worms, various crustaceans, copepods, amphipods, and isopods (that's a lot of pods). Below is a dumbo octopus catching a fish. These creatures have a rather unusual sex life. First of all, there is no distinct season for breeding. Why? Because, this deep in the ocean, seasons don't have any significance. Not only that, but food is often scarce. And the ocean is a huge place! So these octopuses rarely encounter each other. So when a male does occasionally encounter a female, he uses a special protuberance on one of his arms to deliver a sperm packet into the female's mantle. The female then stores the sperm in her body and uses it when she happens to detect that her environment is favorable for laying eggs (kind of like putting a cookie in your pocket and saving it for later when you might get hungry). And, amazingly, the females usually have numerous eggs stored, and these eggs are at different stages of development, so that the female is ready with mature eggs whenever conditions happen to be right to fertilize the eggs and lay them (it's time to get that cookie out and munch on it). The female typically lays her eggs attached to the bottoms of rocks on the ocean floor. In the photo below you can see the eyes of the developing embryos within the eggs. Amazingly, scientists aboard a research vessel in 2005 were able to observe a baby dumbo octopus hatch out of an egg in a dish. It was the first time such a thing had been witnessed and filmed. Check out this video of the newly-hatched octopus! Notice how huge the "ear fins" are when these creatures are this young. And check out this video of an adult dumbo octopus. One more fascinating tidbit. Dumbo octopuses have hairy arms. Well, they aren't really hairs. They are actually called cilia, and they protrude from the octopus's suckers. There are several theories for the purpose of these cilia. First, it is likely they are used in feeding. When the octopus is sitting on the ocean floor, these cilia produce a slight but steady current of water in the direction of the octopus. It is thought that this can lure prey closer. Also, the cilia act kind of like whiskers. When the octopus feels the area around it, the cilia serve as tiny antennae to help find prey. And finally, the octopus uses the cilia to aerate the water around itself, both for its own benefit and to provide more oxygen for its eggs. The cilia produce a current, which pulls oxygen-rich water in from its surroundings to replace the water from which it has already depleted the oxygen. You can see the cilia in the photo below. So, the dumbo octopus deserves a place in the. E.A.H.O.F. (Exquisite Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word Exquisite has had several meanings over the centuries. It originally came from exquisitus, a Latin word meaning "choice" or "chosen with care." When it was first used in English, it meant "anything brought to a highly-wrought condition." This included bad things (such as torture) as well as good things (such as art). Finally, in about 1580, it took on its modern meaning, which is "of consummate and delightful excellence." So, exquisite is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Praying mantis in threat posture - Wikimedia via Sunoven Dumbo octopus #1: MBARI via Ocean Conservancy Dumbo octopus #2, swimming - Oceana.org Dumbo octopus capturing fish - Ocean Exploration Trust via NautilusLive Dumbo octopus eggs - Albers Dumbo octopus showing cilia - Octolab.tv |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed