|

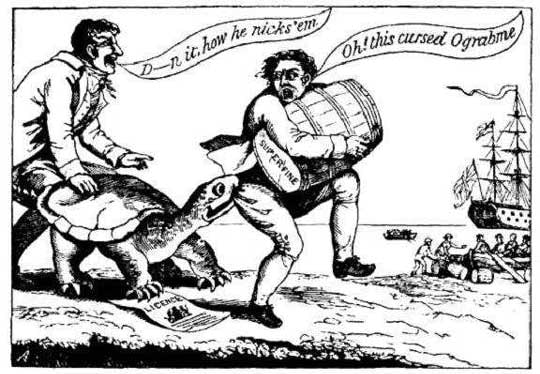

Last summer when I was on a week-long adventure the Boundary Waters Canoe Area with my brothers, nephew, and my son, I got out of the tent one morning to find an enormous female snapping turtle trying to lay eggs right in the middle of the campsite (see photo below). She stayed in that spot for several hours, ignoring us as we took photos and stepped around her as we went about our business around camp. And here's the best part: When the turtle was apparently finished with her attempt to dig her hole, she headed back toward the water. The problem is, this campsite is fifteen feet above the water surface, with a large slab of rock sloping down toward the water. The turtle went straight for a place where the rock gets really steep the last ten feet to the water. She reached a point at which the slope was too steep to walk, and she hesitated. She seemed to consider this conundrum for a few seconds. Then she lunged forward and literally tumbled end over end until splashing into the water. To fully appreciate this amazing behavior, you must realize that this turtle was huge, at least 30 pounds, which made for quite a splash. So what the heck is a Common Snapping Turtle? The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) is a large, heavy water turtle that lives throughout the eastern half of the United States and southern Canada. In fact, North America is the only place on Earth where members of this family can be found. Although there are four species in the family, the common snapping turtle is the most widespread (hence the name, common). I intentionally included the word "common" in the name for this email to distinguish this turtle from the larger Alligator Snapping Turtle, which lives in the southeast U.S. Snapping turtles are perhaps best known for being aggressive when provoked. They have extremely long necks (the species name is serpentina because their neck and head resembles a snake), and they can very quickly snap out and bite with their powerful, beak-like jaws. In fact, a few years ago I found one crossing a gravel road. I approached it to get a better look. Thinking I might move it off the road, I reached for it. The turtle didn't like that. Its head shot out at least twelve inches, and it literally leaped six inches off the ground in an attempt to bite me. I nearly fell over backward in my attempt to pull my hand back. But of course I should point out that these turtles are NOT aggressive unless they feel threatened. If you leave them alone, they will leave you alone. Amazing facts about Common Snapping Turtles They are big! Common snapping turtles regularly grow to over thirty pounds (13.6 kg), and the heaviest one caught in the wild was 75 pounds (34 kg). Its close cousin, the Alligator Snapping Turtle can grow to 300 pounds (136 kg)! They can live for a long time. Their average lifespan in the wild is about 30 years. But a long-term mark and recapture study in Ontario, Canada, suggests that they can live over 100 years. Snapping turtles are not picky eaters. In fact, these turtles will eat just about anything they can fit in their mouths. They eat insects, worms, leeches, crayfish, snails, frogs, other turtles, snakes, fish, small ducklings and goslings, and just about anything they find that is already dead. Last week, we had a stringer of fish tied to a branch at the lake shore so that we could cook them for dinner. We went out for a paddling outing on the lake. As we returned, nearing the shore, Trish, who was in the front of the canoe, suddenly slapped the water with her paddle and cried, "get away from our fish!" A huge snapping turtle had eaten almost all of one of the fish and was trying to start on a second. Trish scared it away with her paddle (I must admit, she startled me, too), but the turtle was back a few minutes later, not willing to give up, so we went ahead and cleaned the fish for an early dinner. Snapping turtles lay lots of eggs. This is about the only time they come out of the water. The female finds a soft bit of ground and uses her hind feet to dig a hole. She will then lay 25 to 45 eggs, which look similar to ping pong balls but have a soft, leathery shell. The eggs hatch after incubating for 75 to 95 days. Now, here's a weird fact about snapping turtle eggs. As is true for some other reptiles, the sex of the turtle hatchlings is determined by the temperature of incubation. At lower temperature (68º F, 20º C) all the young will be female. At higher temps (about 74º F, 23.3º C) they will all be male. And in between, half of them will be male and half female. Hatchling snapping turtles have a low success rate. Only about an inch long, they have soft shells and are quickly eaten by birds. If they make it to the water, many are then eaten by fish or other snapping turtles (hey, that's cannibalism!). Snapping turtles hibernate during the winter. When the temperature drops to below 41º F (5º C), they bury themselves in the mud at the bottom of shallow water and remain there until the spring. That's a long time to hold your breath! Of course, during the winter their metabolism drops to nearly zero, so they don't use much oxygen. Here's part of their secret: while hibernating, snapping turtles take in a small about of water through their cloaca (um... that's their butthole), and they get their small amount of oxygen that way. Even under normal warm conditions, they can hold their breath for over ten minutes! Check out this video comparing the Common Snapping Turtle to the Alligator Snapping Turtle Below is a common snapping turtle, but I don't recommend holding them this way, as they can reach their head back surprising far to bite. One more tidbit. Thanks to a 19th-century political cartoon, the common snapping turtle is also known as "Ograbme." The cartoon was drawn in 1808, and it was in protest to Thomas Jefferson's unpopular Embargo Act. In the cartoon, we see the president prompting a snapping turtle to bite the hind end of some poor merchant, who curses the ograbme (which is "embargo" spelled backward). So, the snapping turtle deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F. (Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious originated in the Disney movie, Mary Poppins. It describes anything so indescribable that there is no other word to describe it. The song is forever etched into my memory: "It's Supercalafragilisticexpialidocious, even though the sound of it is something quite atrocious, if you say it loud enough you'll always sound precocious, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!" So, it's another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Boundary Waters snapping turtle laying eggs - Stan C. Smith Snapping Turtle with mouth open - Tortoise Trust Baby snapping turtle - u/AnotherDee on Reddit Man holding snapping turtle - Ontario Parks Political Cartoon - Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

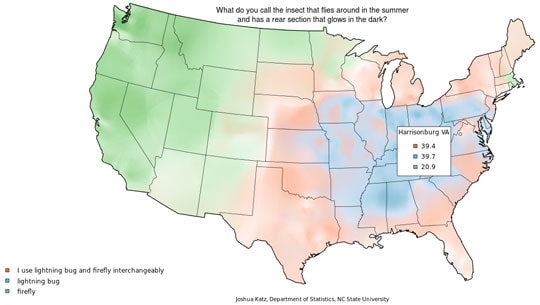

Recently we had the pleasure of having several of our granddaughters visit us for a few days. Two of them came up from a town south of Houston, Texas. The girls, aged 4 and 8, rarely have a chance to see fireflies because they don't seem to have these amazing insects near their home. So, of course, we spent a few evenings chasing them and putting them into bottles to observe before letting them go. It was a real hoot to watch the girls chasing them down. At one point, the four-year-old, Billy, saw one of our solar lights come on and she darted over to it and tried to grab the firefly that she was sure must have landed on it. So I have to ask myself--at what point do we stop enjoying these simple pleasures? Does it happen when we turn thirty? Forty? Is it possible to never lose the ability to enjoy simple things like chasing fireflies on a carefree summer evening? I'm fifty-eight. But I have a lot to learn from my grandkids. In honor of the beautiful summer evenings we've had lately here, today's awesome animal is the firefly! It's time to learn more about this amazing luminescent creature. Some of you may live in areas that may not have fireflies, or perhaps you have other creatures (or fungi) that produce light. But here in the midwest US, fireflies can be seen by the hundreds on warm summer evenings. So, what the heck is a Firefly? Fireflies, often called lightning bugs, are neither flies nor bugs ("bug" is actually the name for insects in the order, Hemiptera, such as assassin bugs and stink bugs). Instead, they are beetles (beetles are in the order, Coleoptera). Astoundingly, there are 2,100 species of fireflies worldwide (although only some of them can light up). All of these species are in the family, Lampyridae. The family name, Lampyridae, comes from the Greek "lampein," which means to shine. I find it interesting that, in the United States, there are distinct regions where people call these beetles fireflies and other regions where they are called lightning bugs. In fact, a study was done by Bert Vaux, a linguistics professor. He surveyed 10,000 people across the country regarding what they call these beetles. The resulting map is below. In the green area, people call them fireflies. In the blue area, they call them lightning bugs. And red is where they use both names. What do people call these insects where you live? Amazing facts about fireflies Fireflies can light up (well, duh). It is a process called bioluminescence. You have to admit, this is a pretty cool superpower, right? Here is a very basic description of how it works. Fireflies have a substance in their abdomen called luciferin (yes, the name has the same Latin root as Lucifer). When luciferin mixes with calcium, oxygen, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a chemical reaction occurs that creates light. Even more amazing, this is the most efficient light we know of. In this chemical reaction, almost 100% of the resulting energy is released as light. In comparison, with an incandescent light bulb, only about 10% of the energy is released as light (the rest is released as heat). The larvae of fireflies are wingless, and they typically live underground (although some live in water). The larvae can also light up, and in many areas, they are called glow worms. In some species, even the eggs glow! But the larvae and adults light up for a different purpose. The main reason adults light up is to attract mates. But the main reason the larvae light up is to warn predators away. You see, fireflies have horrible-tasting defense chemicals in their blood. Predators see the light and then avoid eating these insects. These yucky chemicals have the awesome name, lucibufagins. See the firefly larva below. Check out this video of firefly larvae. We used to think adult fireflies would light up mainly to warn predators to not eat them. But now we know the primary purpose (for the adults) is to attract mates. What's really cool is that each species has it's own specific light signals, so that they don't accidentally get attracted to the wrong species. The signal could be a steady glow, a specific flashing pattern, or even a specific color. The light may be green, yellow, or orange. There is even a species that lives in the Eastern US that glows blue. In the larval form, fireflies are predators, feeding on worms, other insects, and snails. Once they become adults, some are predators while others feed on nectar or pollen. Some species, once they become adults, don't eat at all... they don't even have mouths! Obviously, these adults have one single purpose: to find a mate. Once they accomplish that, they soon die. I imagine not being able to eat gives them a real incentive to be quick about it! Female fireflies of the genus Photuris have a nasty trick. They emit light in the specific pattern of the females of another species. This fools the males of the other species into eagerly approaching, thinking they are about to get lucky with a female of their own species, only to be gobbled up by the trickster. Females of the insect world (and spiders, for that matter) can be mean! The photo below is a female Photuris feeding on an unsuspecting male. One of the most spectacular light shows from fireflies is that produced by those species that flash in sync with each other. Following a predictable pattern, they will all flash at once. This will be followed by several seconds of darkness, and then they will all flash again. Oddly, we aren't sure why some fireflies flash synchronously. It might be because this gives the males a better chance when the female can compare and pick out the best male light (the one that is brightest, maybe?). Check out this video of synchronous fireflies. Unfortunately, fireflies seem to be declining. One reason for this could be the increase in light pollution. Studies have shown (and it just seems logical to me) that artificial lights make it harder for fireflies to find their mates. Also, habitat destruction could be a factor. Fireflies aren't very resilient. When a field is paved, instead of moving to another field, the fireflies simply disappear forever. One additional factor might be that fireflies are collected in large numbers for their luciferase, which is useful in medical research. So, the firefly deserves a place in the A.A.H.O.F. (Amazeballs Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word amazeballs may have come from Amazeballz, which is the name of a pastry shop that started in Plano, Texas (USA). They make miniature cake balls. During the last few years, I've heard people use this word to describe something that is beyond amazing, as in, "The new Star Wars movie is amazeballs!" So, amazeballs is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Cora and Billy catching fireflies - Stan C. Smith Firefly #1 (Japanese firefly) -National Wildlife Federation Firefly name map - NC State University Department of Statistics Firefly larva - Till, via whatsthatbug.com Predatory female firefly - AmazingLife.bio Fireflies in the forest (Japan) - Miyu |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed