|

Turtles are strange reptiles with ribs that are modified and fused to their backbone to form a hard external shell across their back. Turtles can pull their head inside of their shell, and turtles as a group can be divided into two subgroups based on how they pull their head into their shell. Most turtles and tortoises pull their head straight back into the shell. However, there is a group of turtles, called the Pleurodira (the side-neck turtles), that pull their head into the shell sideways. Because they pull their head in sideways, this allows these turtles to have longer necks. The photo below, of a Siebenrock's snake-neck turtle, shows how this works. By folding the neck to the side, there is room for a lot more neck! What the heck is a Snake-neck Turtle? The snake-neck turtles (family Chelidae) are one of the groups of side-neck turtles, distinguished by their unusually long necks. These turtles are restricted to the southern hemisphere, found in Australia, New Guinea, Indonesia, and South America. Snake-neck turtles live mostly in water, and they can stay submerged for long periods of time. They are predators, and the long neck helps them grab prey animals with their mouth. Often, the neck on these turtles can be as long as the turtle's shell. Amazing Facts about Snake-neck Turtles First we need to talk about that long neck. When grabbing fish, snails, crustaceans, tadpoles, insects, and various other invertebrates, this neck makes it easier for the turtle to reach out and quickly snap up a meal. They use a feeding strategy called strike-and-gape. When their nose gets close to their prey, they open their mouth quickly and lower their hyoid bone. This creates a vacuum inside their throat, which sucks in water, along with the prey animal. Check out this video on snake-neck turtles. These turtles spend a lot of time resting on the bottom of streams, rivers, and swamps, and this long neck also serves as a snorkel. Without having to swim anywhere, the turtle can extend its neck to the surface every now and then when it needs to take a breath. They also spend a lot of time basking in the sun to warm up their body and speed up digestion. Let's take a closer look at the two main groups of turtles, the side-neck turtles (Pleurodira), and the "hidden-neck" turtles (Cryptodira). As I stated above, the most obvious difference between these two groups is the anatomy of the neck. Hidden-neck turtles retract their neck into their shell by bending their neck into an S-shape vertically (it looks like an S from the side). Side-neck turtles bend their neck in a S-shape horizontally (looks like an S from directly above or below). This may sound like an insignificant difference (like the stars on the Sneetches in the Dr. Seuss book). However, this difference is only one indicator of anatomical differences that have distinguished the two groups of turtles since the early Jurassic, 200 million years ago. That's how long the two groups have been separated evolutionarily. In other words, they are not closely related at all. There are about 360 living species of turtles in the world today, but only 65 of those are side-neck turtles. The others are hidden-neck turtles. Only 16 of the side-neck turtle species are specifically considered snake-neck turtles, characterized by exceptionally long necks. An example is the broad-shelled snake-neck turtle pictured below. Snake-neck turtles are polygynandrous, which means both the females and the males often have multiple mating partners each mating season. Therefore, during the mating season, males are extremely active, moving as much as possible in their attempt to increase their chances of finding multiple mates. The males have an elaborate courtship, in which they bob their head up and down. If they successfully impress a female, mating takes place in the water. When females are ready to lay their eggs, they locate a suitable spot where they can dig a hole near the water, lay their eggs in the hole, then cover it back up. They lay 8 to 24 eggs, depending on the species and on environmental conditions. After an incubation period of up to 150 days, the young hatch, dig their way to the surface, and head for the water as quickly as possible. The young are vulnerable to predators, and many do not make it to adulthood. Those that do survive often live over thirty years in the wild, and even longer in captivity. Below is a hatchling snake-neck turtle. So, the Snake-neck Turtle deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Frontline Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word frontline (or front-line) is an adjective that evolved from the two-word noun phrase front line, which, in a military sense, refers to the forefront of a battle or military conflict. Eventually, the words were combined to create an adjective with several meanings. The first meaning is related to the military sense of the phrase front line, meaning "located or designed to be used at a military front line" (example: A frontline ambulance helicopter). The second meaning is more broad, related to "the forefront in any action, activity, or field" (example: a frontline health worker in the pandemic). A third meaning is related to proficiency, something or someone that is cutting edge or at the forefront (example: if I'm having brain surgery, I want it done at a frontline hospital). So, at least in this third sense, frontline is another way to say awesome! Well, kind of. Photo Credits:

- Jumping kangaroo - DepositPhotos - Sidewinder - "Sidewinder With its Head in the Air" by Michael R Perry is licensed under CC BY 2.0 - Dung beetle - DepositPhotos - Komodo dragon - DepositPhotos - Siebenrock's snake-neck turtle on white background - DepositPhotos - Snake-neck turtle, on rock with black background - DepositPhotos - Snake-neck turtle basking on a log - DepositPhotos - Broad-shelled snake-neck turtle - Sam Fraser-Smith, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons - Hatchling snake-neck turtle - Tortoise Town

2 Comments

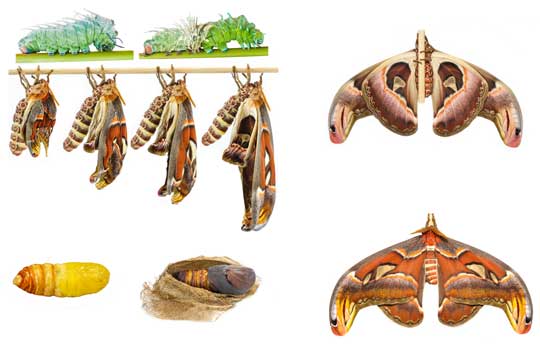

Mimicry in nature has always fascinated me. Viceroy butterflies look like monarch butterflies (to avoid being eaten... monarchs are toxic). Geckos that look like leaves (camouflage). Milk snakes (harmless) that look like coral snakes (venomous). Alligator snapping turtles that have a tongue that looks like a wriggling worm (to attract prey fish). The list of examples could go on forever, and all of them are fascinating. The other day I saw a photo of an atlas moth, and I decided I had to write about it. Not only is this moth impressive for its size, it's one of my new favorite mimicry examples. What do you see when you look at the wing tips of this atlas moth? It's almost unmistakable, isn't it? Each wing tip has a remarkable resemblance to the head of a snake. More specifically, to the head of a cobra, a venomous snake. The resemblance is so striking that the moth's Cantonese name is translated as snake's head moth. Let's explore this awesome animal further. What the heck is an Atlas Moth? The atlas moth is one of the biggest insects in the world, with a wingspan of 10.6 inches (27 cm). And the caterpillars are ginormous too, at 4.7 inches (12 cm) in length. These moths live in tropical forests in Asia, including China, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia. They may have been named after Atlas, the titan god of Greek mythology, but some people believe the name may have come from the way the moth's wings resemble a map. Atlas moth caterpillars are voracious eaters and feed on leaves. Once they metamorphose into adults, however, they don't eat anything at all. In fact, the adults don't even have mouths! Amazing Facts about the Atlas Moth First I want to talk about those cobra images on the atlas moth's wings. To me, it seems quite obvious that this is a wonderful example of Batesian mimicry. This is a category of mimicry in which a harmless mimic resembles a plant or animal that is harmful. The atlas moth is harmless, but it resembles a harmful snake, thus frightening off potential predators. This is also known as a diematic pattern (when a coloration pattern has the result of startling or frightening potential predators). I should point out that some entomologists are not convinced that the atlas moth is mimicking a snake. What?! Are they crazy? Like I said, the mimicry seems obvious to me. Besides the clear resemblance to a cobra's head, I have a few additional arguments to prove it. Argument #1: Batesian mimicry can only evolve if the harmless animal lives in the same geographic area as the harmful animal it mimics—at least at some point in the past. Here in Missouri, we have harmless milk snakes, but we do not have venomous coral snakes. However, when milk snakes evolved a color pattern that resembles a coral snake, the two types would have had to live in the same area, where predators instinctually avoided coral snakes. Coral snakes live in the US, so I am assuming milk snakes gradually expanded their range beyond the range of coral snakes after they evolved this color pattern. The same circumstances would have to be true for atlas moths and cobras. And, in fact, cobras do live in much of the same range as the moths. Argument #2: The cobra pattern on atlas moth wings would only work on predators that rely primarily on vision to hunt. As it turns out, the moth's main predators, birds and lizards, are visual predators. Argument #3: When an atlas moth is threatened, it spreads its wings and moves slowly (and sometimes shakes them), which tends to make the wing tips look even more like two live cobras. Check out this brief video. Are you convinced that the atlas moth's resemblance to cobra heads is mimicry? Or do you think it's a coincidence? Astoundingly, some of the moths have variations in the cobra-head pattern. Look at the example below... this pattern not only makes it look like you are looking at the cobra head from above, it also has white touches that make it look like it is glossy and reflecting the light! Let's take a look at atlas moth reproduction and life cycle. Females lay a cluster of about 150 round eggs, sticking them to the underside of a leaf. After about two weeks, tiny green caterpillars hatch out. They don't stay tiny for long. After eating their own eggshell, they get to work chomping on leaves, eventually growing to 4.5 inches (12 cm) long and 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick. It takes them about 100 days to grow that large. When full grown, the caterpillar will spin a silk cocoon (pupa) attached to a twig. After four weeks in the cocoon, an adult moth emerges. Adult atlas moths are weak, shaky fliers, so they rest during the day. At this point in their lives, they only have one purpose, to find a mate, which they do at night. The adults do not have a mouth and do not eat at all, which means they have to find a mate within a week or two, before they use up their fat reserves and die. The female moth releases a potent chemical to attract males, and males are really good at detecting this chemical—they can detect only a few molecules from several miles away, then they follow the scent gradient until they find the female. Check out this video about the atlas moth life cycle. One last tidbit of information. Because atlas moth larvae are so big, and because they spin silk to create their cocoon, people in some countries use the vacated cocoons as purses. The cocoon, which is extremely strong, is just the right size for a small change purse. All you need to do is sew on a zipper! So, the Atlas Moth deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F. (Superb Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word superb originated in the 1540s, and it meant "noble, magnificent." It came from the Latin superbus, which had more diverse meanings, including "grand, proud, splendid; or haughty, vain, insolent." By 1729, superb was (and still is) primarily used to mean "very fine." So, superb is "an adjective of praise for that which is exceptional." Surprisingly, the word superb did not originate by simply adding a b to the end of the word super. Super is a Latin preposition that means "above." Superb, on the other hand, is actually a shortened form of the Latin superbus. So, superb is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

- Atlas moth #1, hanging on a leaf - DepositPhotos - Atlas moth flying at night - DepositPhotos - Atlas moth, glossy-looking wingtip - DepositPhotos - Atlas moth life cycle - DepositPhotos - Atlas moth cocoons - Elegant Entomology |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed