|

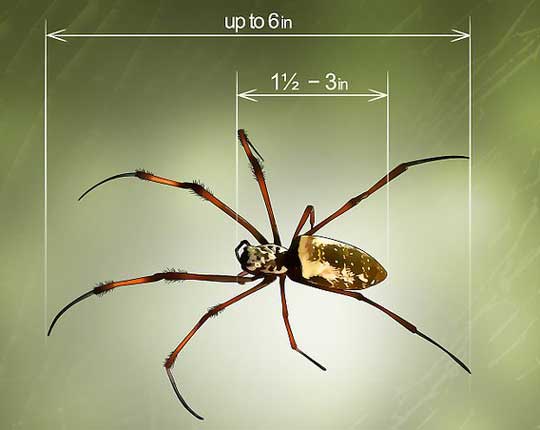

I enjoy featuring animals that show up in my novels. In Diffusion, there is a scene where Samual shows Quentin one of the huge orb-weaving spiders that produce the silk the Papuan natives use to make incredibly strong rope. As it turns out, the spider in my story is not as exaggerated as you might think. Today's awesome animal is the orb-weaving spider, especially the giant golden orb-weaver. So what the heck is an Orb-Weaving Spider? Orb-weavers are a large family of spiders that include over 3,100 species. These are the spiders that typically build large, spiral webs in your garden. Their webs are typically wheel-shaped, and that's how they got the name of orb-weavers (orb general means circular). I am going to focus mainly on the golden orb-weavers (spiders of the genus Nephila). Why? Because they are some of the largest and most beautiful spiders. Below is a photo of a golden orb weaver Trish and I encountered on a hike in Costa Rica: Amazing facts about Orb-Weaving Spiders Some orb-weavers are quite large. The females of the giant golden orb-weaver can have a body length of up to 3 inches (75 mm), and with the long legs included, a entire length of 6 inches (150 mm). But the most striking thing about their size is that the females are HUGE compared to the males. When the male and female of a species are different from each other, it is called sexual dimorphism. But orb-weaving spiders have taken the concept of sexual dimorphism to the extreme. The females can be up to TEN times longer than the males. And this means the male weighs less than 5% of the weight of the female. Wow! Just for kicks, let's convert that to human terms. Let's say there is a 140-pound woman. Her mate would be a man who weighs less than SEVEN pounds. Okay, that's just a little weird to think about. Check out this video of a male and a female golden orb-weaver. There are two main theories for why they are so different in size: Theory #1: In many spiders, once the male mates with the female, he inserts a "mating plug" in the female, which prevents other males from mating with her (I am not making this up!). By doing this, the male can be sure he is the father of all the offspring of that female. But in giant orb-weavers, these plugs do not seem to work. And so the theory is that the females of these species have evolved to be very large so that they can be too large for the plugs to work, thus ensuring that they can produce young from more than one male (more diverse offspring, which is a good thing from the female's perpective). Theory #2: In giant orb-weavers, the males that find and mate with a specific female first will fertilize more of her eggs than males that find her later. And smaller males are faster, so they can scramble around through the vegetation and find females faster than larger males. And thus the males have evolved to have a smaller size. Again, I'm not making this stuff up. See the male and female in the photo below. Well, as you can imagine, for a tiny male orb-weaver, mating with a giant female is risky business. The females have a habit of eating the males after the "job" is complete. But some male orb-weavers have a special strategy to avoid this. It's called mate-binding. To make the females more receptive (and less likely to cannibalize them), the males spread silk over the female's back, in a motion that looks very much like he is giving her a massage. Research shows that this massaging motion makes the female relax, and therefore she is less likely to eat the male. Here is a video of mate binding in orb weavers. Although most orb-weavers are fairly docile, they can certainly bite. But they are not dangerous to humans. They inject neurotoxin, like a black widow spider, but it is much less toxic. As I mentioned earlier, in my Diffusion novels orb-weaver silk is used to make very strong rope. This is actually possible, assuming there is a good way to harvest lots of spider silk, because orb-weaver silk is strong! In fact, it's the strongest biological material we know of. It is more than ten times stronger than a strand of Kevlar of the same diameter. The recently-discovered Darwin's Bark Spider, a type of orb-weaver, has the strongest silk of any spider. They create webs that are more than 80 feet (25 meters) wide! The actual circular part of the web (the part that catches insects and other small animals) can be a meter in diameter. See the Darwin's bark spider web below. In Diffusion, Samuel Inwood made his vest from orb-weaver silk. Actually, few people have been able to do this, as spider silk is not easy to collect in large amounts. In 2012, a textile designer and an entrepreneur collected golden orb-weavers from the wild and managed to get enough silk to create a beautiful cape, which was put on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (see photo below). It took over three years to make! So, the orb-weaving spider deserves a place in the H.S.A.H.O.F. (Heart-Stopping Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The first-known use of the phrase heart-stopping was in 1888. It is possible that it started as a reference to the (incorrect) assumption people used to have that one's heart would stop when sneezing. Today it refers to anything that is so frightening or emotionally gripping as to make one's heart seem to stop beating. I like to use it in a positive way, though, to describe something amazing or exciting. So it is another way to say awesome. Photo Credits: Golden Orb-Weaver on fingers - Stan C. Smith Golden Orb-Weaver Size Diagram - WikiHow Male and Female Orb-Weavers - National Geographic Darwin's Bark Spider Web - Wikimedia Commons Orb-weaver Silk Cape - Wikimedia Commons

1 Comment

Wolfman ?

9/24/2019 03:50:09 pm

There's a number 1 male spider that I will be catching again as a pet I had one last time named d'angelo he was the most dominate male spider ever I would feed him bugs I would put rival male spiders like the wood spider male and he'beat them everytime. This time I will get one and I want to see it beat a male orb weaver spider.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed