|

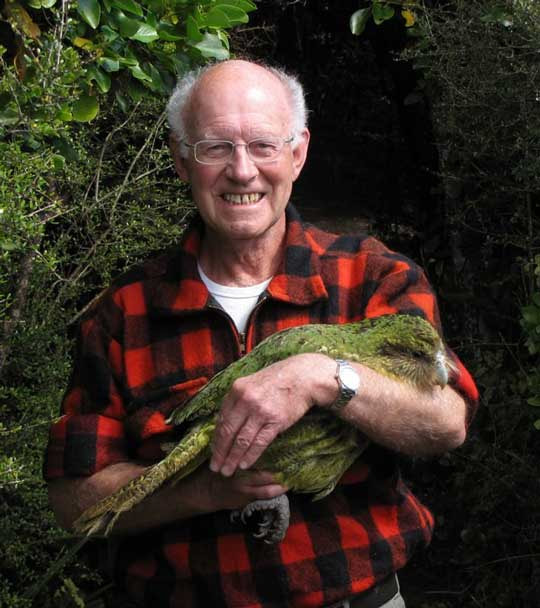

Thanks to reader (also one of my former 7th grade life science students) Scott Finley for suggesting this Awesome Animal. Way back in 1995, Trish and I had a marvelous opportunity to travel to New Zealand. At a zoo there, we had our first introduction to the weird and wonderful kakapo (pronounced KAH-ke-poh), which is perhaps the most unusual of all parrots. These large parrots displayed endearing personalities, and we were immediately enamored by their appearance and antics. I think you'll find them just as fascinating as we do. What the heck is a Kakapo? For one thing, the kakapo is nocturnal—the only nocturnal parrot. And it is flightless—the only flightless parrot. Kakapos are massive, nine-pound parrots—the world's heaviest parrot. They spend their nights waddling around on the forest floor and climbing trees to find their favorite fruits and seeds. To top it all off, the kakapo might be the world's longest-living bird, with some individuals living up to 100 years. Kakapos are endemic to New Zealand, and unfortunately they are highly endangered. In fact, I suppose Trish and I were lucky to see them at all—when we were there in the mid 90s, only 51 individual kakapos remained. The number is now closer to 200, which is good, but the species' survival is still far from assured. The photo below gives you an idea of the kakapo's size. Amazing Facts about the Kakapo A flightless parrot? Really? Yep, completely flightless. Although this is the only flightless parrot, other birds have also evolved to be flightless on oceanic islands where there are few predators. Historically, New Zealand had no large land predators, resulting in a variety of flightless birds that would otherwise be vulnerable, such as the kakapo, several species of kiwi, three species of penguins, the takahe, the weka, and several species of flightless teal (teal are a kind of duck). In addition, New Zealand was home to a variety of extinct flightless birds, including the huge, impressive moas, which were the tallest birds known, able to reach foliage 12 feet (3.6 meters) off the ground. I guess you could say New Zealand is the flightless bird capital of the world. Before humans arrived on New Zealand, the only predators kakapos had to worry about were birds of prey: one species of eagle, one falcon, one harrier, and one owl. Over time, the kakapo became well adapted to avoid these raptors—the parrots developed camouflaged feathers and became nocturnal. When kakapos feel threatened, they freeze, which helps them blend in with their surroundings. Although the eagle, falcon, and harrier only hunt in daylight, the nocturnal laughing owl could still sometimes prey on kakapos. However, the real problems started when humans brought predatory mammals to New Zealand, particularly dogs, cats, and stoats (the short-tailed weasel). Part of the problem is that a kakapo's body has a strong, musty-sweet smell (they use this smell to locate each other). This was not a problem when raptors were their only predators—raptors hunt by sight, not by smell. Mammal predators, on the other hand, have a highly developed sense of smell. Not a good thing for the kakapos! With mammals hunting them, the kakapo's tendency to freeze does not help at all and in fact makes them easy prey. The Polynesian ancestors of the Māori (indigenous people of mainland New Zealand) arrived in New Zealand about 700 years ago, and they brought with them domesticated dogs called Kurī (a now-extinct breed of Polynesian dogs). The Māori used these dogs as a source of food, but they also used them to hunt birds, including the kakapo. Also, the Māori inadvertently brought rats (as stowaways on their boats) to New Zealand, and the rats proliferated and preyed on kakapo eggs and chicks. By the time Europeans arrived in 1642, the Māori had decimated the kakapo in some parts of New Zealand. Then, as I'm sure you can guess, the Europeans greatly accelerated the kakapo's decline. Not only did they clear vast tracts of land, they brought additional mammals, including different dogs, domestic cats, black rats, and stoats. By the late 1800s, the kakapo was recognized as a scientific curiosity, and thousands of them were killed and shipped to numerous museums around the world. As I said above, when Trish and I saw these birds in a New Zealand zoo in 1995, there were only 51 individuals known to exist. Soon after that, all the remaining kakapos were transferred to four islands that had been cleared of all non-native predators and competitors, and were also replanted with native vegetation. Additional ongoing eradication efforts have been because cats, stoats, and rats continually reappear on the islands. These protected kakapos have gradually increased to about 200 birds. Below is a Department of Conservation worker caring for some kakapo chicks. Check out this video about the kakapo. If you watched the video linked above, you saw a kakapo running toward the camera man, then stopping to take a closer look. Kakapos are notoriously friendly birds, and even those living wild on the protected islands are known to come right up to people, climb all over them, and even preen their hair. Of course, this friendly behavior has contributed to their decline, as they are extremely easy for humans and predators to hunt. In addition to hunting and eating kapakos, both the Māori and early European settlers kept these birds as pets. Let's finish this up with a bit about the kakapo's sex life, which is just as unusual as all their other characteristics. Kakapos are the only parrots to have a a polygynous lek breeding system. That's a mouthful, so let's break it down. Polygynous means that one male mates with numerous females, but those females only mate with the one male. A lek is when a group of males gather in one area to compete for females by carrying out elaborate displays and behaviors. Females pick out their preferred males as the males display, or lek. Amazingly, mating occurs only once every five years! This coincides with the ripening of a specific type of conifer seed called the rimu fruit, which kakapos love to eat. When it is finally time, the males will walk (remember, they can't fly!) up to four miles (6.4 km) to get to the lekking arena. At the arena, before the females arrive, the males fight aggressively for the best locations within the arena (each location is called a court). The most dominant males get the best courts. Each court is a bowl-shaped depression in the ground, previously dug by male kakapos. The court bowls are usually situated near large rocks, a dirt bank, or tree roots that act to amplify sound. Why? Because the male kakapos make a lot of noise to impress the females. In fact, males make a loud booming sound all night long (about 8 hours non-stop), every night for a four-month period of time! The booms can be heard up to 3.1 miles (5 kilometers) away. This is such exhausting work that the males often loose 50% of their body weight during these four months (now you see why they only do this when abundant rimu fruits are ripe). As you can imagine, this booming activity can attract non-native predators from a long distance. Darn those non-native predators! Once a female approaches a male's court, he performs an elaborate dance to impress her. Once they mate, the female heads back to her own territory, and the male keeps right on booming, hoping to mate with as many additional females as possible. Females don't even reach sexual maturity until about nine years of age, and they only breed once every five years, so the kakapo is one of the slowest-breeding birds. This is why conservation efforts to increase the population have been so slow. Below is a kakapo chick. So, the Kakapo deserves a place in the N.A.H.O.F. (Neat Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The word neat originated in the 1540s, and it meant "clean, free from dirt." Originally it came from the Latin nitidus, with the literal meaning "gleaming." In the 1570s, it took on the meaning "inclined to be tidy," and in the 1590s the meaning "in good order." In about 1800, it began to be used to describe liquor that was "straight, undiluted." Finally, starting in 1934, neat was being used to mean "very good, desirable." The slang variant "neato" appeared in the 1960s. Today, neat is often used as a whimsically outdated adjective (see the silly "neature walk" videos). How neat is that? That's pretty neat! So, neat is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Kakapo on ground - "Kenneth' Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Kakapo held by man - Errol Nye, National Kakapo Team, DOC. [email protected] by Ppgardne at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Kakapo hiding on the ground - "Hugh' Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Kakapo chicks being fed - Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons Kakapo chick - "K1', Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō)" by TheyLookLikeUs is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed