|

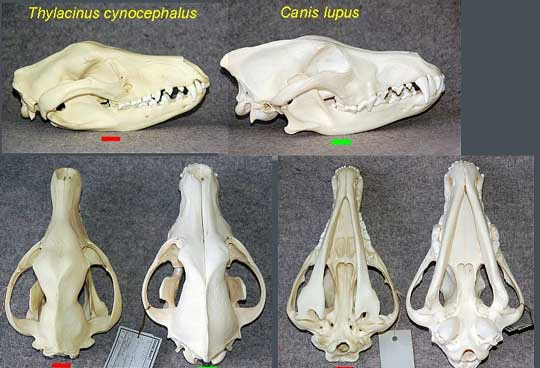

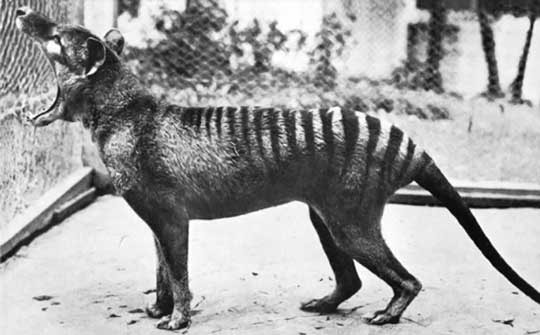

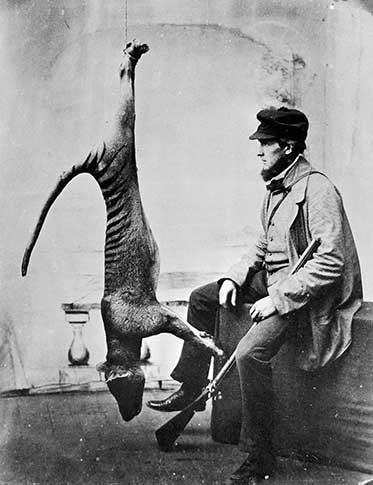

You know, there are some animals that humans really wish still existed. One example is the ivory-billed woodpecker in North America. The last universally-accepted sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker was in Louisiana in 1944. But diehard birders never stop searching, hoping to be the first to discover that this species still exists. And there are numerous unconfirmed sightings. So I guess the ivory-billed woodpecker is kind of like Elvis. In Australia, and particularly in the Australian island state of Tasmania, people are still looking for the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the Thylocine. Yep, they're still looking, even though the last of these creatures died in 1936. The Tasmanian tiger is, no doubt, an awesome animal, so let's take a closer look. We'll also take a closer look at the never-ending search for this creature. What the heck is a Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine)? First, the thylacine is a marsupial. You know what marsupials are, right? They are a group of mammals that give birth to very small young, which are then nurtured in an external pouch (includes kangaroos, koalas, opossums, wombats, and many more). Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, nurture the fetus inside the body, with a placenta that helps exchange nutrients and waste between the mother's blood and the fetus. The thylacine is one of the largest known carnivorous marsupial (marsupials that prey on other animals). At one time, the thylacine was fairly common in Tasmania, New Guinea, and throughout the Australian mainland. The thylacine was what we call an apex predator, which means it was at the top of the food chain in its range (it had no natural predators). Although the thylacine is not related to dogs, it has a general dog shape. Because of this, it is sometimes called the Tasmanian wolf. The name Tasmanian tiger comes from the row of stripes on its back. Amazing facts about the Thylacine The thylacine is one of only two marsupials in which both males and females have a pouch. You already know what the female's pouch is for. The male's pouch serves as a protective covering for the external reproductive organs. Wait, what? That sounds like a no-brainer. Why don't all male mammals have those? Anyway, the only other marsupial that has this protective pouch in males is the water opossum. The thylacine is a great example of what we call convergent evolution, in which unrelated creatures end up having similar structures because they have become well adapted to similar niches. The thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog has filled in other areas of the world. That's why it looks similar to a dog! The skull below on the left is from a thylacine, and the skull on the right is from a timber wolf. Notice how similar they look, even though they are not closely related at all. Since these creatures went extinct in the 1930s, we don't know much about their behavior. But from early recorded observations, we know that they ran with an odd, stiff gait, which made it difficult for the animal to run very fast. Occasionally they were also observed hopping on their back legs like a kangaroo. It is thought that they used this hopping motion when startled. The thylacine also had an amazing ability to open its mouth, spreading its jaws to 80 degrees! Here's a 1933 photo of a thylacine yawning (which is a threat gesture). What a mouth! How did the thylacine go extinct? As stated above, thylacines once lived throughout mainland Australia and in parts of New Guinea. They went extinct in these places about 2,000 years ago. Although there is disagreement as to how the creature went extinct on the mainland, it is thought to be at least partly due to the arrival of the dingo (a dog native to Australia). But more recent studies suggest it may have been caused more by climate change and by the way Aborigines used the land. The dingo theory is debatable because the two animals are thought to have different hunting habits and prey. Why does this matter? Because if they had different prey, they probably did not compete with each other as much as we once thought. However, the thylacines that had been isolated on the island of Tasmania escaped this fate (maybe because there are no dingoes on Tasmania). Even so, only about 5000 thylacines still lived in Tasmania when the first Europeans settled on the island in 1803. This is when things really went downhill for the Tasmanian tiger. Soon after Europeans settled on Tasmania, they started complaining that thylacines were killing their sheep. Actually, there was more evidence that feral dogs and poor farming habits were really the culprits, but the farmers must have decided that the thylacine was easier to blame. By the 1830s, the farmers pooled their money and established a system of bounties for killing thylacines. And then the government started awarding bounties. By the time this practice ended in 1909, a total of 2,180 bounties had been awarded. Below is a photo of a hunter posing with his "trophy" in 1869. This excessive hunting, combined with habitat destruction, the introduction of foreign diseases, and competition from feral dogs decimated the population, and the last thylacine in the wild was shot in 1930. At that time there was a shift in public opinion about thylacines, and preservation measures were put in place. But—you guessed it—this was far too late. Just 59 days after the species was granted "protected" status, the last individual in captivity died at the Hobart Zoo. Its name was Benjamin, and it died because the zookeepers accidentally locked Benjamin out of his sheltered sleeping quarters on a very cold night (I should point out, though, that these details about the name and the accident are now being challenged and may not be accurate). Here is a photo of Benjamin, taken in 1936, not long before he died: People are still searching for Tasmanian tigers Ever since the thylacine's extinction, many Australians have searched for these animals. In fact, some have devoted their entire lives to the search. But no definitive evidence has ever been found. No definite photos, no definite videos, no definite sightings by highly-qualified scientists. You might be tempted to equate this with the search for Bigfoot in North America, or the search for "Nessie" in Loch Ness in Scotland. But... remember that the thylacine is a REAL animal, and it definitely lived only 83 years ago. Is it likely to be alive? Probably not. Is it possible? Absolutely. And what's interesting is that people have consistently reported sightings over the last 80 years. In Tasmania, hundreds of unconfirmed sightings have been reported. Astoundingly, 65 sighting have been reported on the Australian mainland, particularly in the southwest portion of Western Australia. And more recently sightings have been reported in northern Queensland. But... not one single confirmed photo, video, or sighting. Hmm... What do you think? With all the technology we now have, especially trail cameras, wouldn't we have at least ONE definitive video or photo? Perhaps the most intriguing video was captured by teacher Paul Day. Paul was photographing the sunrise in the Yorke Peninsula in northern Queensland when a creature ran across a field in front of him. The creature's strange hopping gait is much like what observers have described for the thylacine. Check out the video! I know, we all want to believe the Tasmanian tiger still exists. How cool would that be? But, perhaps we should remain skeptical, at least until someone comes up with undeniable proof. Again, what do you think? So, the Tasmanian Tiger deserves a place in the. B.O.A.A.H.O.F. (Bit of Alright Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The phrase bit of alright, as far as I can tell, is mainly used in Australia (making it especially suitable for the thylacine) and Great Britain. Typically it is used to describe someone as physically attractive (Example: "He's a bit of all right, isn't he?" said Isadora, looking at a tall man near the door.). Well, the Tasmanian tiger, in my opinion, is a very attractive creature (as extinct marsupials go), so bit of alright is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Tasmanian tiger #1 - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via National Museum Australia Thylacine and wolf skulls - Wikipedia Tasmanian tiger yawning - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via University of Melbourne Tasmanian Tiger (Benjamin) - Getty Images via Foxnews.com Screen shot of Paul Day's Video - National Geographic

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed