|

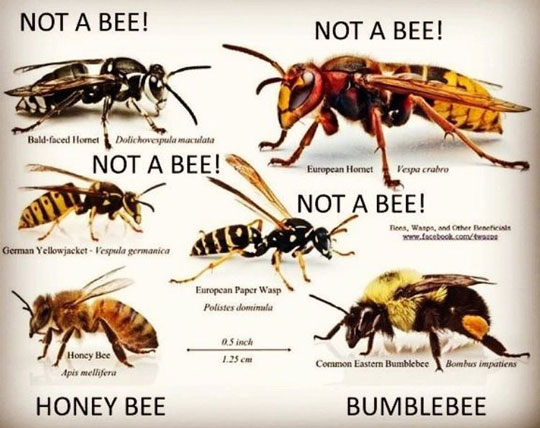

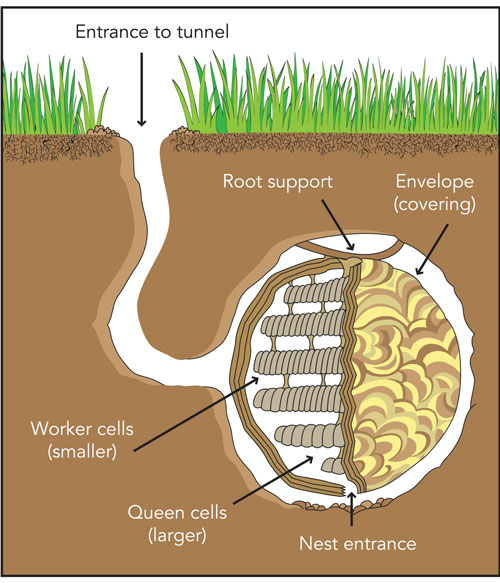

In my last newsletter two weeks ago I featured the prairie dog because prairie dogs make a (very surprising) appearance in my new novel Hostile Emergence. I'm continuing that theme with another animal that appears (in large numbers) in the new book. This animal is the yellowjacket. What the heck is a Yellowjacket? Yellowjacket (or yellow jacket) is the name used to refer to a group of wasp species that are predatory and live in social colonies. Yellowjackets are fairly small wasps, and they typically have yellow and black markings. Something I can tell you about them from personal experience—yellowjackets are mean, and their stings are painful! Amazing Facts about Yellowjackets Okay, first we need to sort out exactly what yellowjackets are, compared to other bees and wasps. Sometimes people mistakenly call them bees because they are about the size of a honeybee. Bees are different from wasps in a number of ways. For example, bees are plump and hairy compared to wasps. Wasps are slender, with a very thin waist. Wasps are shiny, with a smooth body surface. Bees have thick hind legs for collecting pollen, wasps do not. When wasps fly, their legs hang down, but bees' legs are tucked against their body. Bees have a barbed stinger, which usually causes the stinger to pull loose from their body after they sting, so they can only sting once (which is why they are less aggressive than wasps). Wasps can sting over and over again (so they tend to be much more willing to sting). Bees feed on flower nectar and pollen, whereas wasps are predators that kill other insects and take them back to their nest to feed to their young (although they feed on nectar and sweet fruits when they are not caring for their young). So, now we know yellowjackets are not bees, but what makes them different from other wasps? What makes them different from hornets, for example? This is confused by the fact that some yellowjackets have the word hornet in their name, such as the bald-faced hornet in the picture above. True hornets, though, are much larger than yellowjackets (see the European hornet above). Why does the bald-faced hornet have that name if it's actually a yellowjacket? Good question. Some people call it a blackjacket, which I think would be a less confusing name. One reason bald-faced hornets have been given that confusing name is that they typically make nests that are exposed and above ground (most yellowjackets make nests below ground or in enclosed cavities). Here is a bald-faced hornet nest I found on the back of our garage. Another reason bald-faced hornets have been given the confusing name is that they are black and white, while other yellowjackets are black and yellow. As I said above, typical yellowjackets make their nests below ground (as do the yellowjackets in Hostile Emergence). These below-ground nests usually only last one warm season, then the yellowjackets die off (except for the new queens). During that one season, the nest grows to about the size of a basketball, and can have several thousand wasps. In some areas where the winters do not get so cold, the nests can survive for several years, growing much larger. Below is an excavated two-year yellowjacket nest. Let's imagine for a moment that you are walking across your yard. You do not realize that buried below your feet is a massive yellowjacket nest like the one pictured above. You cannot tell it is there because the tiny entrance hole at the ground's surface is only a centimeter across. Perhaps you see a few wasps flying in and out of the tiny hole, so you stomp on the hole to kill some of them. This is a bad idea. Why is it a bad idea? Because yellowjackets are notoriously aggressive when their nest is threatened. Not only that, but they can detect vibrations in the ground. You might have hundreds of angry yellowjackets swarming out of the hole, ready to sting. This can be a painful experience, and if you happen to be allergic to their venom, it can even be dangerous. Last summer I pushed my mower over a below-ground yellowjacket nest, unaware of the nest's presence. Fortunately, I was stung only three times, but each of those stings resulted in massive swelling for several days. So, even if you aren't terribly allergic to yellowjacket venom, numerous stings can still be dangerous or even deadly. And, as if that weren't enough, yellowjackets can bite as well as sting! They have jaws for capturing their prey, and they can use those jaws to bite you and hang on, making it difficult to swipe them away with your hands. They can cling to your skin or clothing, stinging repeatedly. Nasty little devils! Yellowjackets are actually more aggressive in the fall, as the weather is turning cold. Why? Because, as I said above, the wasps die out when the weather turns cold (except for the new queens). They die because their food source (other insects, as well as nectar and ripe fruits) is disappearing. So, the wasps are starving to death. This makes them grouchy, because they are constantly working harder to find enough food. In the spring, there are fewer yellowjackets, and they have plenty of food, so they are not as aggressive. Yellowjackets also have a bad habit of attacking valuable honeybee colonies. They target honeybees, killing and eating all the adults and larvae, then feasting on the honey for dessert. This is more likely to happen in the fall, when honeybees are more sluggish in the cold compared to yellowjackets. In Canada there was a report of yellowjackets wiping out 100 of the 300 beehives of a commercial beekeeper. Each of those colonies had 50,000 honeybees! You're probably wondering if I have anything good to say about yellowjackets. I do. After all, they are Awesome Animals. Some of the awesomest of all animals are those that can be dangerous (sharks, venomous snakes, and black widow spiders, to name a few). Sometimes an animal's most amazing adaptations are those of self defense and predatory skills. So, although I have a healthy respect for yellowjackets, I still appreciate their amazing characteristics. I'll point out that many of the insects yellowjackets prey on are considered agricultural pests. Yellowjackets may not be beneficial to honeybee colonies, but they are beneficial to farmers. Yellowjackets also often feed on human garbage, typically items with high sugar content. Let's wrap this up by examining the fascinating life cycle of these insects. Yellowjackets are social wasps, meaning they live in colonies in which individuals have specific roles, with specific body types for each role. Yellowjacket roles include queens (females), workers (females), and drones (males). In climates with a cold season, a colony typically lasts only one year. A colony is started by a single fertilized queen. After surviving through the winter in a sheltered place, a queen will find a suitable place to start a nest, usually an existing hole in the ground (like a rodent burrow), but sometimes in a cavity of a stump or even a house or barn. She will build a small paper nest and lay about 50 eggs. After the eggs hatch, she hunts insects and brings the food back to feed the larvae. When the larvae are full grown, they form a pupa and eventually emerge as adult females (workers). As more workers emerge, they get busy and start expanding the nest. They also go hunting for food for the new larvae, and they defend the nest (all yellowjacket females can sting, but the male drones can't). The colony and nest continue growing, often resulting in 5,000 wasps and a nest with up to 15,000 cells. Eventually, the workers start creating larger cells, in which new queens will grow, as well as male drones. The new queens and the drones then leave the nest and go out into the world to mate. After mating with new queens from other colonies, the males quickly die. After mating with drones from other colonies, the new queens store up body fat and find a safe place to survive the winter. All the wasps, except for the new fertilized queens, will then die. The nest decomposes over the winter (the wasps do not reuse the nests). In the spring, the new fertilized queens start the cycle all over again. Check out this video about the yellowjacket's nest and life cycle. Note: although yellowjackets typically build their nests below ground, sometimes a queen will start a colony in a cavity of a human-made house or other structure, as you will see in this video. So, the Yellowjacket deserves a place in the G.A.H.O.F. (Groovy Animal Hall of Fame). FUN FACT: The term groovy originated in the jazz culture of the 1920s. It probably originated from the physical groove in a record, in which the needle drags. However, it was mainly used to refer to the groove of a song (how the song sounded and felt to the audience). Disc jockeys would say things like, "I'm going to play some good grooves" (or "hot grooves"). Eventually, starting in 1941, the word groovy began to be used as slang, meaning "marvelous, wonderful, or excellent." This usage became really popular in the 1960s, but by the 1980s it was only being used as a humorously outdated term. I still hear people using the word, especially people much younger than myself, so perhaps it will become popular again. So, groovy is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Yellowjacket #1 (on white background) - DepositPhotos Stock Images Large excavated yellowjacket nest - Wikipedia Creative Commons License Cartoon yellowjacket - DepositPhotos Stock Images Yellowjackets on apple core - DepositPhotos Stock Images Yellowjacket nest diagram - Marin/Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District

1 Comment

Adam

2/26/2021 10:45:46 am

My first yellow-jacket experience: Four years old in the woods of Mississippi. Saw a pretty, yellow insect vanish down into a hole. Dropped a pebble down after it to to coax it back out so I could see it. Got plenty of yellow jackets to see. They clung to me, stinging, as I ran most of the way through the woods back to my house.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Stan's Cogitations

Everyone needs a creative outlet. That's why I write. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed